Library of Congress

Library of CongressCadets at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point during the Civil War.

What do James B. McPherson, Quincy Gillmore, Douglas MacArthur, Wesley Clark, and Mike Pompeo have in common? They were all outstanding military scholars and graduated first in their class at the College of West Point. Nevertheless, by the end of their military and political careers, each had a disparate reputation as a soldier and leader, sometimes involving controversy.

Academic performance is considered a consistent predictor of future career success, whether it be in accounting or the military. Class rank and grade-point average aren’t the only metrics considered—the same is true of other types of student performance, which is why professional sports leagues hold drafts every year.

One of my favorite issues of The Civil War Monitor (Fall 2018) included an article (“Building the Perfect Army”) that creatively combined two seemingly incompatible subjects: Civil War leadership and fantasy football. This wasn’t an article about the actual Civil War draft, but about a fictional Civil War draft of another variety. “Building a Perfect Army” asked five well-known historians to participate in a draft to create their own imagined Civil War fighting forces, selecting army, corps, division, artillery, and cavalry commanders in an effort to build the best imaginary army. Their efforts were graded by three more judges, also noted historians.

The results seemed like an excellent data set to evaluate the overall reputations of the officers selected for each of the position categories. Who did these historians and judges think was the best army commander from the war? The best cavalry officer? Who would you pick to command your artillery? After all, not only were historians making the picks, but other historians were judging those picks.

The army commanders chosen in the opening rounds held few surprises (picks in order of selection with judges’ average draft grades in parentheses, 10 being the highest possible rating): Ulysses S. Grant (10), William T. Sherman (8.7), George G. Meade (7.7), Robert E. Lee (9), and George H. Thomas (8). Same with the corps and division commanders: Winfield Scott Hancock (9), Thomas J. Jackson (8.7), John B. Gordon (8), James Longstreet (9.7), and John Gibbon (8.3); Phil Kearny (8.7), Patrick Cleburne (9.3), J.C. Robinson (8), Cadmus Wilcox (7.7), and William Mahone (8.3). The artillery and cavalry draft also contained familiar names: Henry Hunt (9.7), E.P. Alexander (9.3), John Pelham (8.3), John Pegram (8.7), and John Mendenhall (7.7); Phil Sheridan (8), John Buford (8), James Wilson (7.3), George A. Custer (7.3), and J.E.B. Stuart (8.7). It’s noteworthy that while the judges rated Stuart as the best cavalry commander available in the draft, he was the last one selected by the historians.

Those 25 officers represent the best tactical and strategic leaders from the Civil War and the best of the best—those selected in the first three rounds and ranked highest by the judges—were Grant, Hunt, Longstreet, and Cleburne. The blue-chip prospects coming out of this draft also offered the most fantasy value. But with most drafts, fantasy value is based on potential, and this selection took place 150 years after the careers of the draftees had ended.

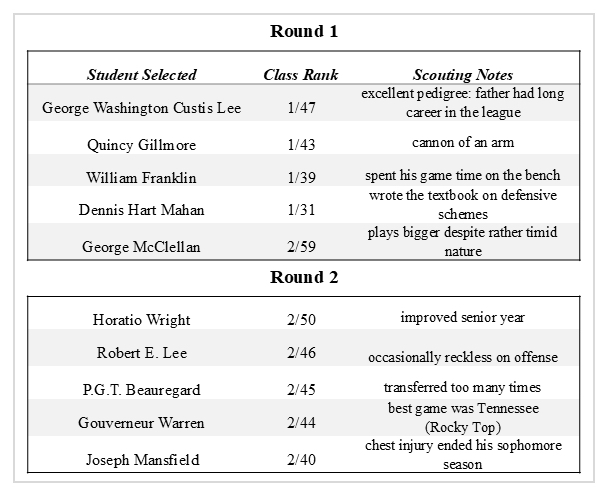

What if this exercise had been conducted more like a professional sports draft, not a post hoc fantasy? What if we were picking future officers—West Point graduates, regardless of year—as if this were a college draft day, in which projected potential was suggested by academic performance and reputation? Had this been the case, the first two rounds would have looked something like this:

The last player taken in the National Football League draft is often labeled “Mr. Irrelevant.” In the case of this draft of West Point graduates, that distinction would have gone to George Armstrong Custer, who graduated ranked 34th in a class of 34.[1]

In the Monitor draft, there were only five “teams.” In the NFL, there are 32 teams making picks. In the Civil War there were, so to speak, only two teams making selections. So which side landed the better haul of “draftees,” the Union or the Confederacy? To determine a grade for a Union or Confederate pick, two things must be known: the final class rank of the student and the size of the graduating class (competition faced in college). The “best” picks are the highest ranked students in a very large class; the lowest potential value is found in poor students at the bottom of larger classes. A student who finishes first in a class of 50 graduates has slightly more eventual potential (value) than one who graduates at the top of a class of 25—more competition equates to a bit more (future) potential value.

To determine the potential value of a pick, we’ll use their class rank, while also taking into account the size of their competition (the size of the class from which they graduated). Each overall graduating class has the same potential value (arbitrarily set at 100 points). Each graduating student gets a fraction of these 100 points (draft rank/class size). Robert E. Lee graduated 2nd out of a class of 46 students, so he earns many points (he graduated higher than 44 other cadets, so he gets 44/46 = 96% of the potential 100 points). Ambrose Burnside graduated 18th of a class of 38, a rather ordinary class ranking. He gets 18/38ths of the potential 100 points, or around 50%. Had his graduating class been larger (perhaps 50 or 60 students instead of 38), his potential value would have gone up slightly to reflect this greater competition. In short, the formula for calculating draft potential takes into account the class rank and the size of the class, rewarding future officers for finishing at the top of large classes.[2]

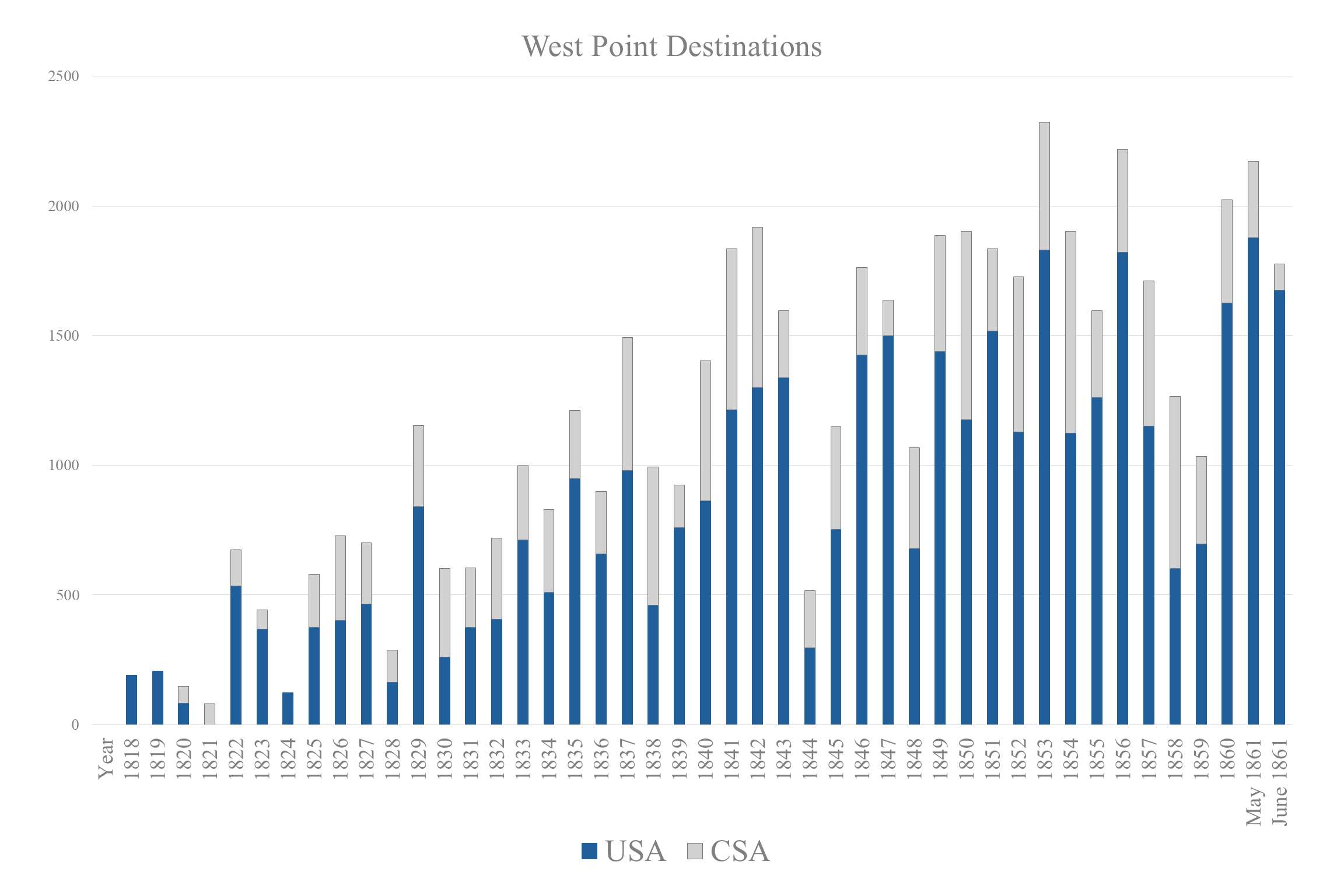

Just over 1,000 cadets who attended the United States Military Academy at West Point between 1818 and 1861 went on to serve during the Civil War. Of these men, more than 70% fought for the Union (Figure 1). If quality of draft potential is considered instead of strictly its quantity, the Union has an even greater advantage (38,122 vs. 14,638 class ranking value points—Federals enlisted 72% of the talent available). Remember, too, that almost two-thirds of the men who fought, both officers and common soldiers, did so for the Union. All of this means that, on average, the Union had slightly more draft picks from West Point than might be expected based on army size, and they enlisted players with slightly more leadership potential (average class rank value points [vp]: Union 53.1, Confederate 49.1).

Scott Hippensteel

Scott HippensteelFigure 1. Choice of army, Union or Confederate, for West Point graduates, Classes of 1818–1861. The Y (vertical) axis represents “total value points” (vp).

How could this deficit in class rank points be so marked in Confederate officers? Using my formula, for every P.G.T. Beauregard (96.6 vp), Custis Lee (98.9), and Robert E. Lee (96.7), you find a James Longstreet (4.6), Earl Van Dorn (8.1), and Henry Heth (1.0). Notably, the West Point graduates who best represent their eventual army’s average draft value are familiar names: for the Union, John Sedgwick (24/50, 53 vp) and Ambrose Burnside (18/38, 53.6 vp); for the Confederates, Albert Sydney Johnson (23/42, 46.2 vp).

All of this draft discussion deals only with potential, not eventual performance on the (battle) field. There are always college athletes with poor pedigrees who are taken late in the NFL draft and eventually make it to the Hall of Fame (Tom Brady, picked 199th, or James Longstreet, class rank 54/56). There are also top prospects who go bust (JaMarcus Russell, first pick in the 2007 draft, Ryan Leaf, second pick in 1989, Braxton Bragg, 5/50, 91.0 vp, or George McClellan, 2/59, 97.6 vp).[3]

So, returning to the Monitor’s 2018 draft: Had the historians been making picks based on West Point pedigrees rather than Civil War performances, who would have had the best draft? The panel of judges gave Ethan Rafuse’s army the best draft grade for his selection of Lee, Gibbon, Kearny, Mendenhall, and Buford. One would expect that Rafuse, who was at West Point then as visiting professor of military history, would win the fantasy West Point draft as well. Turns out his draft was solid with respect to West Point class rank value points (97.6, 48.4, 53.4, and 58.9 = average 64).[4]

Jennifer Murray’s draft was judged the worst. She selected Meade, Jackson, Wilcox, Pelham, and Sheridan (67.1, 72.2, 79.9, 35.6).[5] Note that this average value is the same as the draft winner’s 64 value points. Draft potential doesn’t always correlate with eventual reputation, and vice versa.

Several of the officers drafted were educated at institutions other than West Point. For example, the last pick in the draft, William Mahone, graduated 8th in a class of 12 from the Virginia Military Institute. There were several other high-ranking officers from VMI and The Citadel that escaped our 1861 rankings.[6] Not surprisingly, the Confederacy drafted more than 99% of the men educated at these southern military schools.[7]

When we make our way through the judges’ rankings of the best and worst of the 2018 Monitor draft, the results are unexpected and surprising. U.S. Grant (judges’ lone consensus score of 10, 47.2 vp), Henry Hunt (9.7, 39.7 vp), and James Longstreet (9.7, 4.6 vp!) were all taken in the first two rounds. The bottom three judges’ scores go to George G. Meade (7.7, 67.1 vp), James H. Wilson (7.3, 86.4 vp), and George Custer (7.3, 1.0 vp!). That’s an average West Point draft potential of 30.5 for the judges’ top three picks and 51.5 for the bottom three, and without Custer in this draft, the contradictory results would have been even more striking.

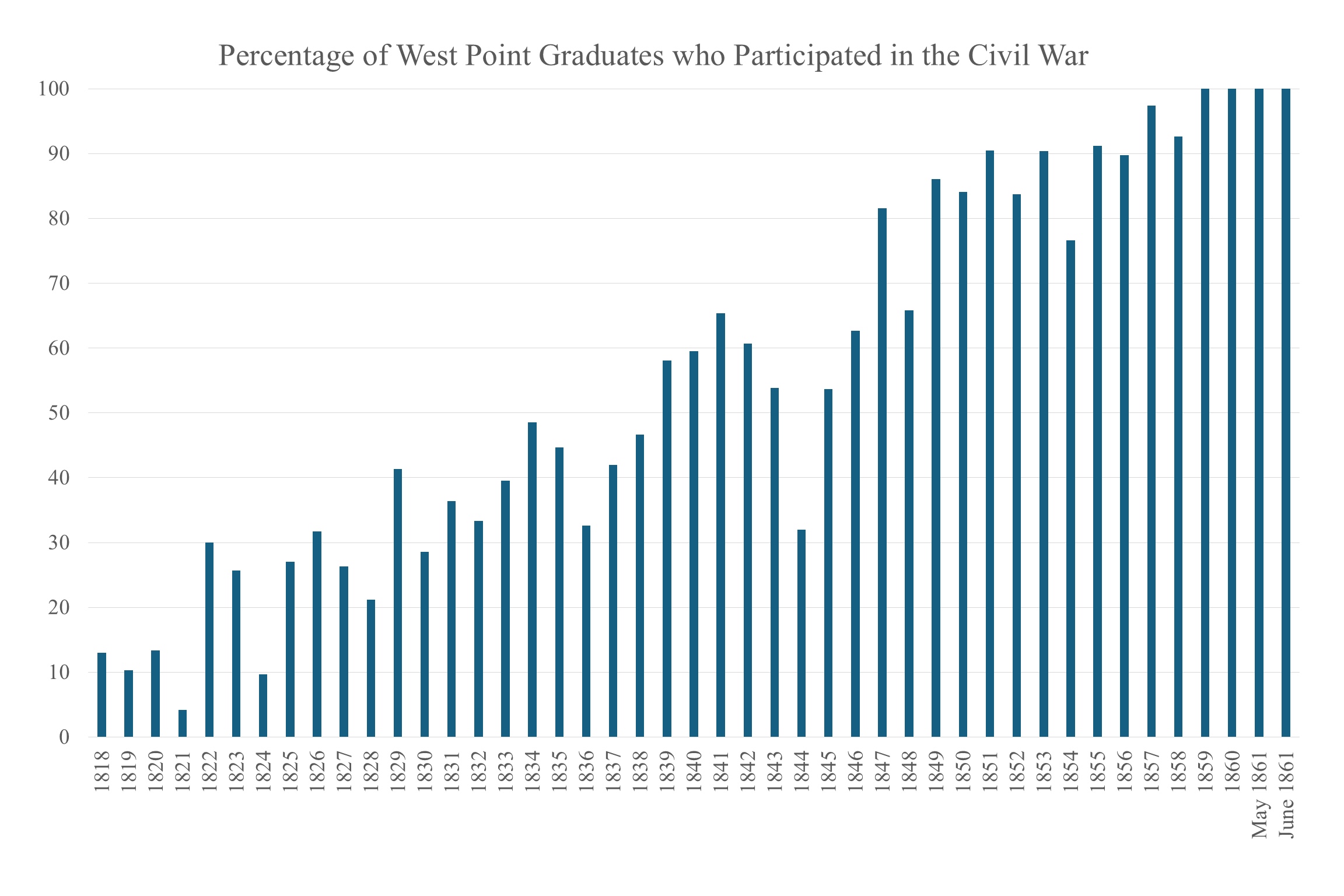

Can we say which was the best West Point draft class of all time? The most valuable class was one in which many students graduated and fought in the Civil War (Figure 2). The class of 1853 saw 47 officers selected with 2,324 points of potential value (Figure 1). The Union got James McPherson (99.1 vp), John Schofield (87.5), and Philip Sheridan (35.6), while the Rebels got John Bell Hood (16.4)—a bit of a mismatch. Another class that strengthened the Federals was 1856’s, as they got more than 75% of its graduates and 82% of its potential value.

Scott Hippensteel

Scott HippensteelFigure 2. Percentage of West Point graduates who fought in the Civil War by year of graduation. Compare this figure with the data presented in Figure 1 and it becomes clear that the Union army was benefiting from getting the greatest percentage of the graduating classes and this majority increased into the 1850s, when more of the graduates would eventually fight in the war.

The Confederates’ best draft class? By percentage of picks, in 1830 they had half the picks and drafted 57% of the value. By total future potential, they successfully drafted more than 700 value points in 1850 and 1854, when they took John Pegram (79.7) and J.E.B. Stuart (73.3).

In a more important context than fantasy, historians have argued for decades about why the Civil War was so bloody, while battles so often proved less than decisive.[8] Some point to the rifle musket “revolution,” others to outdated tactics, and still others suggest that it was the similar training and education of the officers on both sides. Consider the leadership at Antietam: With regard to academic training, you could not have two commanders with more similar potential than Lee (96.7) and McClellan (97.6). Even their subordinates, with one surprising exception, were well balanced by side: Longstreet (4.6) and Jackson (72.2) versus Hooker (43.0), Burnside (53.6), Porter (81.5), and Mansfield (96.0). As military historian Wayne Wei-siang Hsieh (one of the Monitor judges) stated in his book West Pointers and the Civil War: The Old Army in War and Peace, the opposing commanders had a “rough equilibrium in training, competence, and leadership that existed between the two armies” (p. 116). While this may be true at the very top of both armies’ command structures, this brief survey demonstrates the Federal dominance in selecting the majority of the potential leadership talent coming out of the country’s best military educational institution. The dearth of well-educated captains and colonels only became more problematic for the Confederacy after the tremendous and irreplaceable losses suffered among high-ranking officers at the Seven Days Battles, Shiloh, and Gettysburg. As the war ground on, finding well-trained replacements in the southern ranks to compensate for those losses was nothing more than a fantasy.

Scott Hippensteel is professor of earth sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he focuses on coastal geology, geoarchaeology, and environmental micropaleontology. He has written three books about using science to illuminate military history: Sand, Science, and the Civil War: Sedimentary Geology and Combat (University of Georgia Press, 2023), Myths of the Civil War: The Fact, Fiction, and Science behind the Civil War’s Most-Told Stories (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), and Rocks and Rifles: The Influence of Geology on Combat and Tactics during the American Civil War (Spring Nature, 2018).

Notes

[1] “Mr. Irrelevant” might also describe Henry Heth, who ranked 38th in a class of 38. Custer’s class of 1861 was split in two, graduating in May and June.

[2] The formula for determining draft value based on class rank is straightforward: ((1.01 – (draft rank/class size)) X 100). A starting value of 1.01 was used (instead of 1.00) so that students that finished at the very bottom of the class would still have at least a small amount of potential value. Otherwise, cadets like George Custer would finish with zero points (1.00 – 38/38) = 0. It seemed fairer to give Custer at least a little potential value even though he was a terrible student.

[3] I live and teach in Charlotte, North Carolina, home of the lowly NFL Panthers. It was difficult for me to write about quarterbacks selected with the first draft pick who also appear to be colossal busts.

[4] Philip Kearny received his military training at the French Cavalry School at Saumur, France.

[5] John Pelham resigned from West Point in 1861 so has no class rank.

[6] James Lane (2/24), Robert Rodes (10/24), and John McCausland (1/22) all graduated from VMI. Evander Law graduated two years after Micah Jenkins (first in his class) from The Citadel.

[7] Of the 1,827 VMI graduates who fought in the Civil War, only 19 were on the Union side.

[8] We might all agree that there isn’t anything sillier than an imaginary sports team.