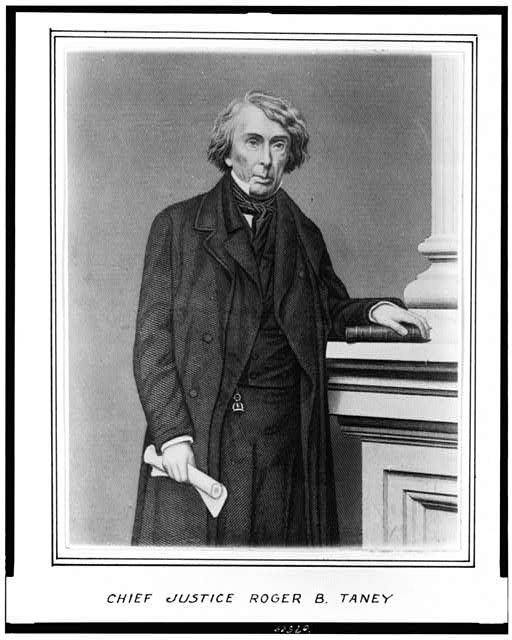

Throughout the Civil War, the highest judicial officer in the United States, Roger Brooke Taney, held sympathies for the Confederacy. In June 1861—before the first major battle of the war—Taney lamented the “paroxysm of passion into which the country has suddenly been thrown.” In that same letter to ex-president Franklin Pierce, he continued, “I hope that it is too violent to last long, and that calmer and more sober thoughts will soon take its place.” He believed that the North and South would be better off with “a peaceful separation, with free institutions in each section.” Having two separate nations would be “far better than the union of all the present states under a military government, and a reign of terror preceded too by a civil war with all its horrors, and which end as it may will prove ruinous to the victors as well as the vanquished.” In other private correspondence, Taney called Union soldiers “vandals” and the new federal currency “paper trash.”

As the Chief Justice of the United States, Taney did what he could to embarrass the Union war effort. On June 1, 1861, he issued an opinion in a case called Ex parte Merryman declaring Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus unconstitutional. Shortly after releasing the opinion, he saw to its publication and distribution. In many ways, Taney’s opinion was legally sound, but there was irony in Taney’s position. Previously he had praised Andrew Jackson’s declaration of martial law in New Orleans during the War of 1812, and as chief justice he upheld the governor of Rhode Island’s declaration of martial law during the Dorr Rebellion in the 1840s.

South of the Mason-Dixon Line, Confederate leaders lauded Taney’s decision in Ex parte Merryman. “The eminent and venerable Chief Justice Taney, . . . whose purity of character and whose great legal ability are acknowledged by all, has in a recent decision clearly exposed the unconstitutionality of the proceedings,” declared Confederate Secretary of State R.M.T. Hunter. Both publicly and privately Confederate president Jefferson Davis echoed Taney’s criticism of that “ignorant usurper” in the North who was “trampl[ing] upon all the prerogatives of citizenship” and “exercis[ing] power never delegated to him.”

Privately, Taney vented his anger not only at the expanding federal power in the North, but also at the public’s acceptance of Lincoln’s actions. “The supremacy of the military power over the civil, seems to be established,” he wrote in a letter to a friend in August 1863, “& the public mind has acquiesced in it & sanctioned it. We can only pray for better times—and submit with resignation to to [sic] the chastisement which it may please God to inflict upon us.” Taney drafted opinions striking down important federal war measures, such as the Legal Tender Act of 1862 and the 1863 conscription law. He kept these opinions in his desk, ready to issue them at a moment’s notice. But the right cases never came before his bench, and the opinions sat unused, only to be discovered after his death. Sitting at his home in the nation’s capital, Taney wished he could “escape the foul & corrupt atmosphere of Washington.”

In his eighties, Taney seemed to be hanging on much longer than most observers thought he ever would. In July 1863, Ohio senator Benjamin F. Wade quipped, “I prayed with earnestness for the life of Taney to be prolonged through Buchanan’s Administration,” so that that Doughface president would not be able to replace him. Wade wondered if he might have prayed a little too hard and “overdone the matter,” for it was now appearing that Taney might outlive Lincoln’s term in office, too.

But as the war dragged on, Taney’s strength seemed increasingly to fail. In January 1862, he remarked that he was “afraid to venture out” onto the slippery streets of Washington. Being confined to his home much of the time, he found that he had difficulty holding a pen “and suffer much pain if I sit long at the desk.” During one bout of illness, he wrote that he was “now only so far recovered as to be able to walk a few times across my room—and have then to sit down and pant for breath.” By July 1864, he wrote despondently that he was too sick to visit Baltimore and “must therefore remain at home, with all the discomforts of this Town & await with patience and resignation whatever providence may have in store for me.”

As death approached, Taney needed great assistance to continue his work in court. “The last time I saw him was after the final adjournment,” remarked the reporter of the Supreme Court in October 1864, “when somebody was administering whiskey & water to him in the Judges rooms to keep him ‘up,’ after his effort at presiding.” Taney finally died on October 12, 1864—the first day of a two-day referendum in which the voters of Maryland abolished slavery in their state. General Nathaniel P. Banks remarked that “the elections carried him off.”

Many in the North rejoiced. “The Hon. old Roger B. Taney has earned the gratitude of his country by dying at last,” wrote New York City diarist George Templeton Strong. “Better late than never.” Noting the irony that the long-time defender of slavery died on the same date that slavery would perish in Taney’s home state, Strong concluded, “Two ancient abuses and evils were perishing together.” The eminent Lincoln scholar Don E. Fehrenbacher similarly noted that the chief justice’s death “put an end to the anomaly of a nation’s fighting a war with its highest judicial officer bound in sympathy to the enemy.”

In February 1865 a bill was introduced in the House of Representatives to honor the late chief justice with a marble bust in the Supreme Court’s chamber in the Capitol. The bill quickly passed in the House but was rejected by the Senate. Radical Republican Charles Sumner of Massachusetts argued that “an emancipated country” should not honor the author of the infamous Dred Scott decision. A New Hampshire senator similarly pointed out that Taney “sank into his grave without giving a cheering word or a helping hand to the country he had vainly sought to place forever by judicial authority under the iron rule of the slave-masters.” In short, the chief justice was a traitor who had tried to use the courts to harm the Union. It would not be until 1874 that Congress passed a bill to honor Taney with a bust in the courtroom—and then, it was attached to a bill honoring the now-late Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, Taney’s successor, as well.

Jonathan W. White is an assistant professor of American Studies at Christopher Newport University and the author of Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman (Louisiana State University Press, 2011) and Emancipation, the Union Army, and the Reelection of Abraham Lincoln (Louisiana State University Press, 2014). In 2015 he will publish Lincoln on Law, Leadership, and Life with Sourcebooks, and he is presently writing a history of sleep and dreams during the Civil War. To learn more about his research and teaching, please visit http://www.jonathanwhite.org/.

Selected Sources: Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001); Brian McGinty, Lincoln and the Court (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009); James F. Simon, Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney: Slavery, Secession, and the President’s War Powers (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006); Carl Brent Swisher, Roger B. Taney (New York: Macmillan Co., 1935); Jonathan W. White, Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011).

Illustration Courtesy the Library of Congress (loc.gov).