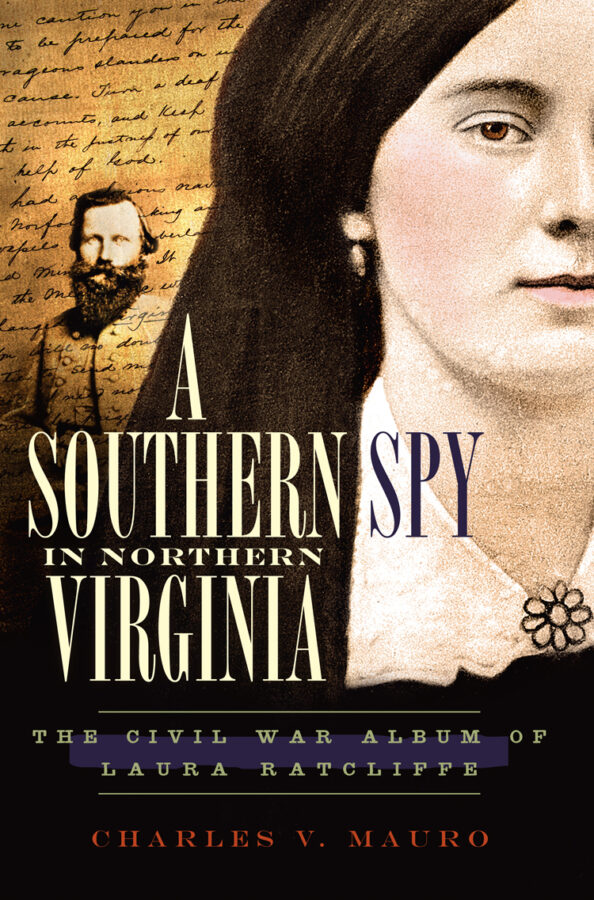

A Southern Spy in Northern Virginia: The Civil War Album of Laura Ratcliffe by Charles V. Mauro. The History Press, 2009. Paper. ISBN: 1596297433. $21.99.

During the Civil War, Confederate brigadier general J.E.B. Stuart gave a leather album to Laura Ratcliffe, a twenty-five year old resident of Fairfax County, Virginia. “Presented to Miss Laura Ratcliffe,” Stuart wrote on the cover page, “by her soldier-friend as a token of his high appreciation of her patriotism, admiration of her virtues, and pledge of his lasting esteem” (53). Within the album’s blank pages Stuart not only copied down two poems for Ratcliffe, but also composed a couple of original poems just for her. By the end of the war, his poems would be joined by the signatures of twenty-six Confederate soldiers and fourteen civilians. This deceptively simple album is the topic of Charles V. Mauro’s most recent book, A Southern Spy in Northern Virginia: The Civil War Album of Laura Ratcliffe. “My intent,” Mauro explains in his introduction, is “to try to clear away the mystery of who these soldiers and civilians were and uncover their relationships to Laura” (9).

During the Civil War, Confederate brigadier general J.E.B. Stuart gave a leather album to Laura Ratcliffe, a twenty-five year old resident of Fairfax County, Virginia. “Presented to Miss Laura Ratcliffe,” Stuart wrote on the cover page, “by her soldier-friend as a token of his high appreciation of her patriotism, admiration of her virtues, and pledge of his lasting esteem” (53). Within the album’s blank pages Stuart not only copied down two poems for Ratcliffe, but also composed a couple of original poems just for her. By the end of the war, his poems would be joined by the signatures of twenty-six Confederate soldiers and fourteen civilians. This deceptively simple album is the topic of Charles V. Mauro’s most recent book, A Southern Spy in Northern Virginia: The Civil War Album of Laura Ratcliffe. “My intent,” Mauro explains in his introduction, is “to try to clear away the mystery of who these soldiers and civilians were and uncover their relationships to Laura” (9).

Mauro’s detailed analysis of Ratcliffe’s Civil War album distinguishes this book from prior works that dwell on her espionage activities. Ratcliffe lived “at the center of a spy, or intelligence-gathering, ring in western Fairfax County,” a network which would monitor Union troop movements and notify nearby Confederates (143). The book begins with an introduction to Ratcliffe’s family, her community, and her childhood before quickly moving into a detailed analysis of the autographs within the album. Mauro highlights the humanity behind the handwriting by offering a short biography of each individual who stood before Ratcliffe and signed the pages. In addition to providing a birth date, synthesis of Civil War activities, and a death date, Mauro also attempted to trace each person’s movements during the war to determine the most likely date that he or she would have signed the book. The result is a compilation of colorful and varied characters who snuck, strolled, and marched into Ratcliffe’s home between 1862 and 1865. Mauro concludes his book with a chapter on Ratcliffe’s postwar years.

Among the signatures are a variety of names, both male and female, famous and obscure. One of the more prominent signatures is that of Fitzhugh Lee, the nephew of Robert E. Lee. Ratcliffe also became close to Confederate cavalry commander John Singleton Mosby and gained his signature. Mosby credited Ratcliffe with saving his life by giving him critical information about Union troop movements that prevented his walking into a trap. As Mosby recalled in January 1863: “I observed two ladies walking rapidly toward me. One was Miss Laura Ratcliffe, a young lady to whom Stuart had introduced me a few weeks before…fortune brought them across my path. But for meeting them, my life as a partisan would have closed that day” (99). In addition to soldiers, civilians signed the album. Mauro’s talent for discovering and telling interesting stories is especially evident in this section of the book. For example, he includes the tale of Mollie and Virginia Millan, two young Virginia girls who fell in love with soldiering brothers. The boys “vowed to return home after the war to marry them,” and they did (147). Mollie lived three miles southeast of Ratcliffe and signed her album at some point during the war.

Ratcliffe did not leave behind a diary, letters, or children to share her story. As the sole item kept and preserved by Ratcliffe, this album’s value cannot be underestimated. Mauro scoured the diaries, letters, and religious sources from her community to piece together Ratcliffe’s life, though holes remain and despite months of research, many assumptions fill the pages. Mauro, for instance, had to assume that Ratcliffe kept the album hidden in her home, speculate that the book was signed during the war, and “make an educated guess” about the exact location of her home during the war (24). “If only theses signatures were dated!” he exclaims at one point (84). Mauro is refreshingly upfront about the speculative nature of many elements of his book. In his conclusion, he admits this “is a story based on a limited amount of evidence provided in a secret album, but whose full details we can only hint at and which will probably never be fully revealed” (191).

Genealogists, history buffs, and northern Virginia residents will enjoy this readable study. Researchers can appreciate the inclusion of full page photographs of many of the letters, poems, and signatures. Mauro is successful in providing an “interesting insight into the intersection of civilian and soldiers’ lives during the Civil War” (190-1). Academic historians, however, will likely finish the book wishing for more. As a book written for a broad audience, Mauro excludes prolonged discussions of historiography. Gender historians might find his passing overview of women in the Civil War to be lacking depth and complexity. Instead of reading this book as a finished study, scholars should see it as a resource from which they can seize missed opportunities. For example, Mauro’s brief comment that Ratcliffe’s father “presumably” died around 1842 is left without further analysis (21). How might the lack of a male protector have impacted Ratcliffe’s life both before and during the Civil War? Is her experience representative of other female households at the time? Further development of the relationship between Stuart and Ratcliffe, a comparison between her activities and those of other women in the area, and a discussion of how Ratcliffe fits into the larger Civil War narrative are all subjects that would benefit from further analysis.

In the poem Stuart wrote on March 3, 1862, he hoped “May grief o’er shadow ne’er my Laura’s brow” (54). This wish for “Fair Laura” would not come true (54). Despite her youth and beauty, she would not marry until 1890, to a wealthy neighbor originally from New York. The marriage lasted just seven years. After her husband’s death, Ratcliffe became so consumed by grief that she decided that she would never kill an animal that had been alive while her husband had lived. Seventeen years later, she slipped, fell, broke her hip, and modestly refused to let a male doctor examine her. For the remaining nine years of her life she laid in bed, surrounded by her cats, until she died at home on August 3, 1923, at the age of eighty-seven. Her album, the sole written record she left behind, reminds readers that women too were veterans of war, taking stories and secrets with them to the grave.

Angela Esco Elder is a doctoral student in history at the University of Georgia.