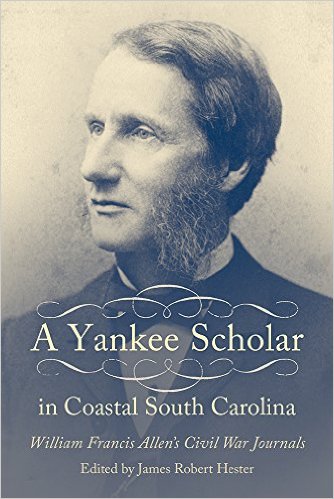

A Yankee Scholar in Coastal South Carolina: William Francis Allen’s Civil War Journals edited by James Robert Hester. University of South Carolina Press, 2015. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1611174960. $49.95.

The so-called Gideonites—the white missionaries and teachers who arrived after federal forces occupied the South Carolina Sea Islands—often wrote about their experiences. A Yankee Scholar in Coastal South Carolina is a most welcome addition to that extensive documentary record. Born in Massachusetts, the Harvard-educated William Francis Allen was, as editor James Robert Hester duly notes, a prototypical Yankee scholar. That simple fact makes his often-lengthy journal entries (customarily mailed home to his family) a worthwhile and unusual source.

The so-called Gideonites—the white missionaries and teachers who arrived after federal forces occupied the South Carolina Sea Islands—often wrote about their experiences. A Yankee Scholar in Coastal South Carolina is a most welcome addition to that extensive documentary record. Born in Massachusetts, the Harvard-educated William Francis Allen was, as editor James Robert Hester duly notes, a prototypical Yankee scholar. That simple fact makes his often-lengthy journal entries (customarily mailed home to his family) a worthwhile and unusual source.

Allen had a knack for describing landscapes, interiors, and people. He wrote well, often sketching out particular scenes with telling detail and, in some cases, remarkable perception. Allen, his wife, and her young cousin arrived on St. Helena Island in November 1863 and remained there less than a year, but the bulk of his journal covers this brief period. As the Civil War was ending in April 1865, Allen journeyed to Charleston, where he served as an assistant school superintendent and again recorded his experiences in a brief journal.

Allen participated in a fascinating labor and educational enterprise (brilliantly interpreted in Willie Lee Rose’s classic Rehearsal for Reconstruction), but just as importantly became a close observer—and therein lies the value of the journals. In an excellent introduction, editor James Robert Hester perceptively concludes: “Always the scholar, Allen saw things through the eyes of the scholar” (19). The journals are quite vivid on geographical detail. Passages on everything from room furnishings to agricultural techniques give the entries a richly detailed quality that pulls the reader into Sea Island South Carolina.

Most strikingly in these pages, the freedpeople often come alive as multi-dimensional human beings. There is a useful appendix of “black St. Helena residents” with names and other identifying information. Allen of course brought his own cultural baggage to bear, but his observations and conversations with African American men, women, and children also caused a rethinking of his own views. He at first described the black children as “something between foreigners and dumb animals” (53), but also noted how many once enslaved people were unfailingly kind and generous. He soon decided that the former slaves were far less degraded than he had expected, but that the barbarities of the institution were far greater than he had assumed. In end, he developed quite positive views of his students’ educational potential and abilities.

Scattered throughout the journals are revealing accounts of the day-to-day triumphs and trials of teaching. Allen often discussed students’ speech patterns, and especially their diction and grammar. Most of these young people had no way of telling time, so his emphasis on punctual attendance often proved challenging. Allen noted problems with discipline and especially fighting. Although he did not cite this explicitly as an effect of slavery, Allen described how so many children were bashful and quite averse to making eye contact. As he came to know the students and their parents, his journal entries became fuller and more illuminating. Even so, he could be rather tone deaf as when he expressed surprise that black men might be reluctant to serve in the Union army or termed the freedpeople a “peasant” population (167). Often occupying the middle ground on contentious political, economic, and social questions, Allen proved to be a cautious reformer, favoring a gradual movement toward former slaves owning land and achieving economic independence.

In many ways, Allen became a kind of anthropologist studying an exotic population (both white and black). In Charleston, he had a number of conservations with ex-Confederates, whom he found more conciliatory than expected but still rooted in their long-held beliefs about slavery and race. He accordingly recounted the declining fortunes of aristocratic families now forced to accept rations from the despised Yankees. Allen was especially interested in music and regularly transcribed lyrics; shortly after the war, he published the important collection Slave Songs in the United States. Students of African American religious history will find helpful material in this volume. Allen listened to praise house singing (and “shouting”) and then offered descriptions of black religious services. Discussions of class differences among the black population along with some interesting comments on various teachers and plantation supervisors rounded out his carefully recorded observations of the South Carolina Low Country.

All in all, A Yankee Scholar in Coastal South Carolina makes for fascinating reading and immediately becomes an important new primary source for studying the Civil War era. James Robert Hester might have appended the articles that Allen wrote for the Nation and the Christian Recorder, but deserves great credit for bringing out such a valuable and extremely well edited volume.

George C. Rable is Charles Summersell Chair in Southern History at the University of Alabama.