In 1918, physician William Keen, who had served as a Union army surgeon during the Civil War, reflected on the surgical conditions he and his fellow military doctors faced in the early 1860s. “We operated in old blood-stained and often pus-stained coats, the veterans of a hundred fights. We operated with clean hands in the social sense, but they were un-disinfected hands.” Still worse, he concluded, “We used undisinfected instruments from undisinfected plush-lined cases…. If … an instrument fell on the floor it was washed … in a basin of tap water and used as if it were clean.”

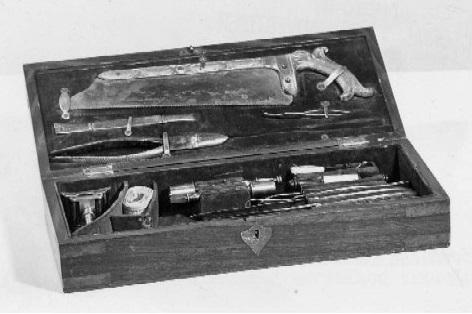

While the conditions that Keen and other surgeons operated in—and the practices that many of them employed—were unsanitary, the tools, some of them shown below, they used were crafted with care and often innovative.

Surgeons used this amputation knife to cut flaps through the muscle of an injured limb—both to expose the bone prior to sawing it off and to use to form the stump after amputation.

The hook-like tip of the tenaculum helped pull back tissue so that the surgeon could better observe what he was cutting with a scalpel.

Galt’s trephine, a conical device with a saw-toothed cutting edge at one end, was used to bore a hole into a patient’s skull to treat a depressed fracture—both to aid in the removal of shattered fragments of bone and to release pressure.

The rigid reinforcement bar on this metacarpal saw—used to provide stability when cutting through the small bones of a hand—could be lifted out of the way (as shown) when deep incisions were required.

The flexible blade of this chain saw was employed when a surgeon wanted to extract a section of bone rather than amputate a limb. It minimized damage to the overlying muscle tissue when cutting through bone. The surgeon operated the device by holding both handles and pulling the saw back and forth across a section of bone.

Hey’s saw, with one rounded and one straight edge, was used to cut into a patient’s skull.

A Petit screw tourniquet—named after the French surgeon Jean Louis Petit who designed it in the early 18th century—was used to prevent a patient from hemorrhaging during amputation. Its strap was buckled around the limb above the wound and tightened by twisting the screw.

These long forceps—known as bullet forceps—were used to extract bullets and other fragments from soldiers who had suffered penetrating gunshot wounds.

The handle of this capital saw—used to cut through long bones in order to amputate a limb—appears to be based on the pattern specified by Richard Satterlee, medical purveyor of the U.S. Army during the Civil War.