“If you want to have a good time, join the cavalry!” Detailing the early war exploits of J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate troops, this song immortalized the daring ride around George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac and raid on Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in 1862. The song’s opening stanza concludes with a catchy, commendatory phrase: “Bully boys, hey! Bully boys, ho!” It probably encouraged more than one southern youth to pick up a gun and go “join the cavalry!”[2]

Soldiering, as the boys soon learned, was far from a bully time. It was a hard life, only infrequently punctuated with small pleasures and moments of respite.

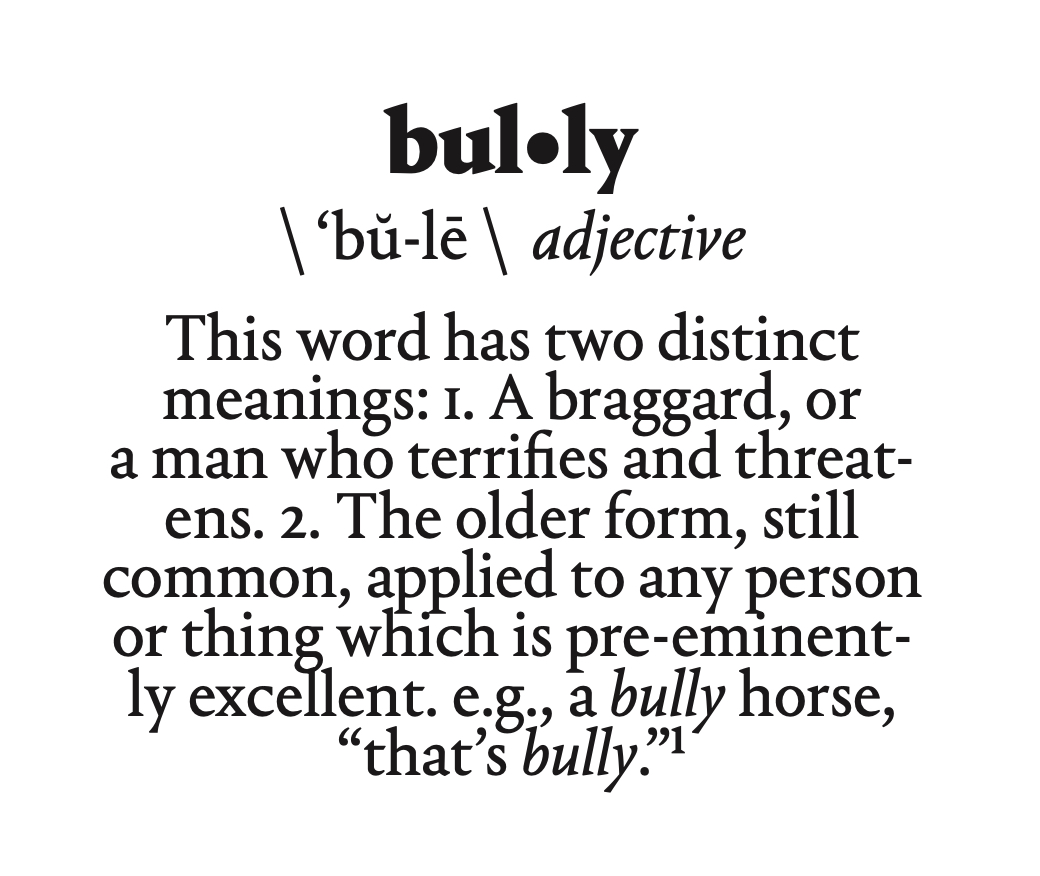

From his desk in New York City, the Irish-born poet Charles Dawson Shanly captured this sentiment. In “The Brier-Wood Pipe,” a young soldier stood watch near camp. “HA!,” he thought, “Bully for me again, when my turn for picket is over; / And now for a smoke, as I lie, with the moonlight in the clover.” Although “but a rough at best,” the boy’s thoughts drifted homeward to the city’s Bowery neighborhood as the pipe smoke wafted upward and dissipated into the night air. Shanly’s poem later appeared in an 1866 anthology, which concisely defined bully for its readers: “[T]he use of ‘bully,’ as an expression of encouragement and approval among our roughs and Bowery boys … is no novelty in the language. The word is found similarly used in the dramatists of the Elizabethan period, and those of the Restoration.”[3]

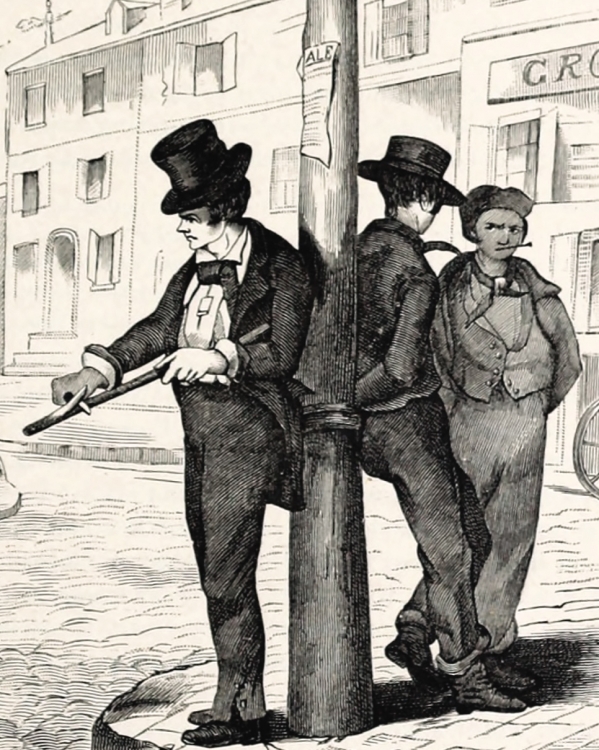

In a postwar illustration, a group of bully boys stands on a street corner in New York City.

Indeed, both bully and bully-rook were used as terms of endearment between male friends in William Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor.[4] In 19th-century America, bully was loosely associated with New York’s Bowery—a neighborhood infamous for its rough-and-tumble saloons, bawdy concert halls, and countless brothels. A nearly history recalled “sidewalks thronged with pleasure-seekers, among them sailors with rolling gait, lusty sleek-haired young butchers, mechanics, flashy girls, and the bully boys from the Five Points.”[5] Given its ties to the city’s underworld, the term could but did not always imply rough or rowdy behavior of some sort or another.

Although used by both Union and Confederate soldiers, bully appeared most frequently among correspondents in the mid-Atlantic region, especially among Pennsylvanians and New Yorkers.[6] Private James S. Jones from Livingston County, New York, for example, “had bully times” when on detached duty near Manassas Junction, Virginia—a stark contrast to his experience just two months before “in the Great Battle of Gettysburg.” Stationed on Cemetery Hill, he recalled when “the shell rained in … tairing up graves knocking monuments & iron fences killing horses & men … there was some noise when those cannons all got to playing.”[7]

The winter holidays, in particular, were a jolly good time for the boys in blue and gray. Savoring a brief respite from the daily grind, Civil War soldiers often had a parcel sent from home or a special meal and a cup of cheer in camp on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s. James F. Goodwin, a private in the 17th Maine Infantry, “had a bully” Thanksgiving in 1864. “I tell you we had … a small peace of pie four apples and two mouthfull of Chicken to a man I tell you they like to killed there self a eating fo the soilders thanksgiving it was so harty.” Yet, his holiday was not as merry as this meal would indicate. Stationed at Fort Rice near Petersburg, Virginia, the men of 17th Maine were hunkered down in felled-log shelters, dodging enemy bullets. “Well Father,” Goodwin wrote, “we have it jest about the same here now as ever[.] we are a peltting a way at the Rebels day and night all of the time.” He wanted “to haft … some tim out” for a while.[8]

Confederate captain Arthur W. Hyatt, meanwhile, found the phrase too crude and classless. “I never ate anything I relished more than I did this bread and butter. It was magdocious.” Magdocious? “The last word of the last sentence is of my own creation,” he wrote, “and is intended to imply the quintessence of goodness. It is also intended as a substitute for the word ‘bully.’ I cannot say the supper was ‘bully’; it sounds even too vulgar for the army.”[9] An 1889 dictionary would have agreed with Hyatt. The word, according to A Dictionary of Slang, Jargon & Cant, was “often applied in a commendable sense by the vulgar.”[10]

The older meaning of bully gradually fell out of common usage. Today, when we think of the schoolyard bully, it’s an aggressive kid stealing milk money and hurling epithets. The Civil War, however, was an era when soldiers sang “Bully boys, hey! Bully boys, ho!”