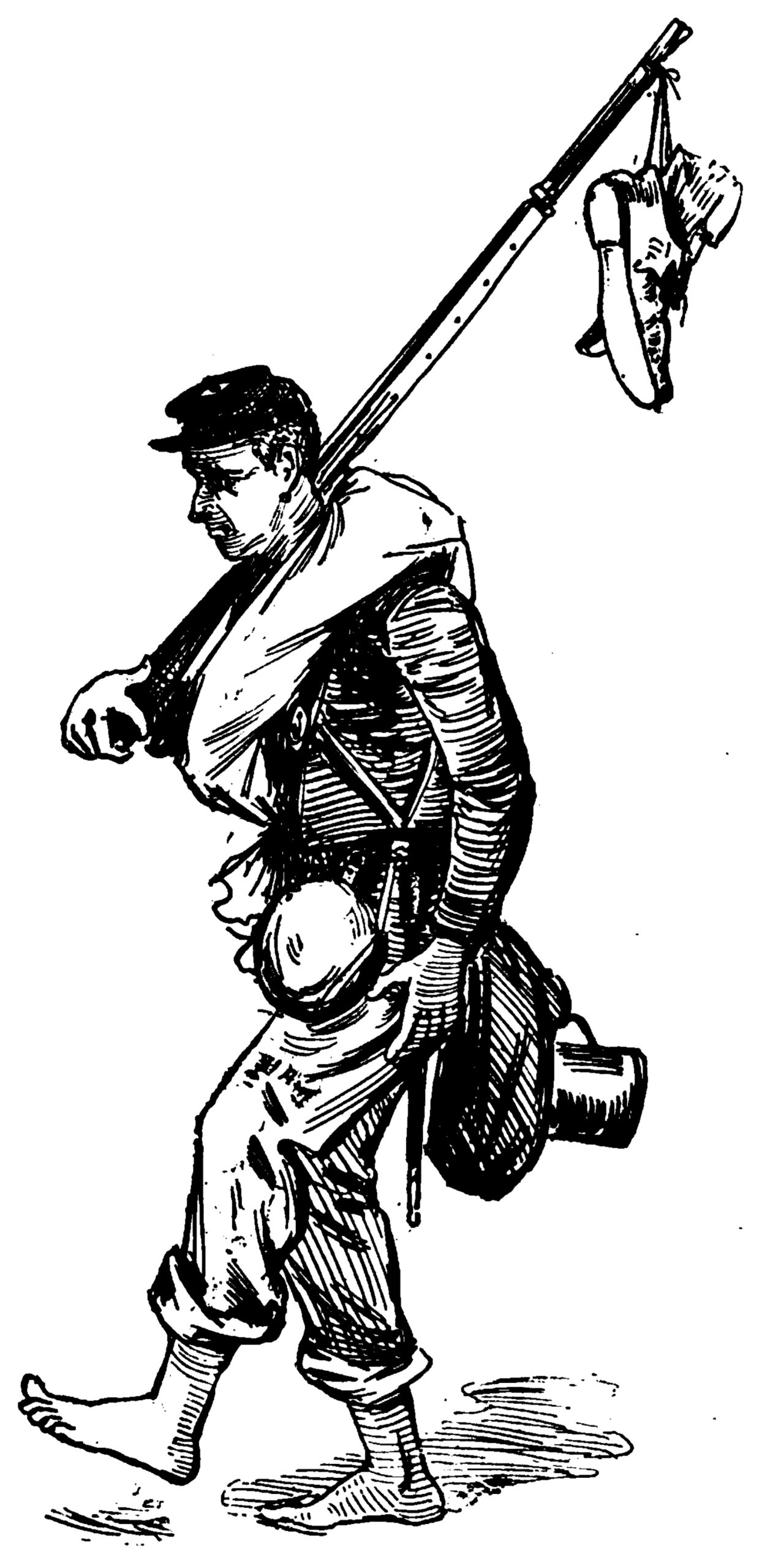

A straggler on the move

In the Voices section of our Winter 2022 issue we highlighted quotes about “straggling” soldiers in the Union and Confederate armies. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that just missed the cut.

“You don’t know how thankful you ought to be that you don’t live in the invaded country. Wherever there is an army, for 10 or 15 miles around it there will be hundreds of stragglers…. They will go into a house and beg what they can and then steal what is left. Rough, dirty, coarse brutes, if they were all shot, our army would be better off.”

—Illinois officer Charles Wright Wills, in a letter home while campaigning in Missouri, March 26, 1862

“I was awoke at daylight by Moses complaining that his valuable trunk, containing much public money, had been stolen from our tent whilst we slept. After a search it was found in a wood hard by, broken open and minus the money…. This is evidently the work of those rascally stragglers, who shirk going under fire, plunder the natives, and will hereafter swagger as the heroes of Gettysburg.”

—British military observer Sir Arthur Freemantle, who had spent the Battle of Gettysburg with the Army of Northern Virginia, in his diary, July 4, 1863

“Since the battle the army had been constantly diminished by sickness or prostration, and by more straggling than I ever saw before. Poor fellows! they could not help it. The men were near the point where further efficient physical exertion was quite impossible. Even the sound of the skirmishing, which was almost constant, and the excitement of impending battle, had no effect to arouse for an hour the exhibition of their wonted former vigor.”

—Union officer Franklin A. Haskell, on the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, in his memoirs

“Strict orders were issued against straggling. No man would be allowed to leave the ranks without a written pass from the Surgeon, and all stragglers were to be picked up by the Provost Guard and taken to headquarters for trial by court martial…. After the first day, no attention was paid to orders. Men fell out in such numbers the Provost could not arrest them, and came straggling into camp until nearly morning.”

—David Lane, 17th Wisconsin Infantry, in his diary, July 29, 1863

Alfred Waud’s “A Straggler”

“This sketch, taken in a little country store, is a fair representation of a class which increases with great rapidity when the army is on the move. With worn-out clothes, mournful looks, and dirty persons, they beg or steal as occasion offers, carefully avoiding their regiments, where they can get all needful supplies, for fear they should be given something to do. They generally travel in little squads, some of whom have thrown away or sold their arms and knapsacks—sleeping in barns or camping out in by-places, for which the modern shelter-tent affords great facilities, being so easily transported and pitched. Sometimes they want for food, but more often live on the fat of the land, begging or buying bread, and stealing poultry, meat, vegetables, and so forth.”

—War artist Alfred Waud, explaining “A Straggler,” his sketch in the March 28, 1863, edition of Harper’s Weekly

“On this march I was a participant in an incident which was somewhat amusing, and also a little bit irritating. Shortly before noon of the first day, Jack Medford, of my company, and myself, concluded we would ‘straggle,’ and try to get a country dinner. Availing ourselves of the first favorable opportunity, we slipped from the ranks, and struck out. We followed an old country road that ran substantially parallel to the main road on which the column was marching, and soon came to a nice looking old log house standing in a grove of big native trees. The only people at the house were two middle-aged women and some children. We asked the women if we could have some dinner, saying that we would pay for it. They gave an affirmative answer, but their tone was not cordial and they looked ‘daggers.’ Dinner was just about prepared, and when all was ready, we were invited, with evident coolness, to take seats at the table. We had a splendid meal, consisting of corn bread, new Irish potatoes, boiled bacon and greens, butter and buttermilk. Compared with sow-belly and hardtack, it was a feast. Dinner over, we essayed to pay therefor.”

—Leander Stillwell, 61st Illinois Infantry, in his memoirs

“[W]e … had a great number of stragglers attached to us. The stragglers demonstrated very clearly this morning that they had strayed from their own regiments because they did not want to fight. My men fought gallantly until the stragglers ran and left them and began firing from the rear over their heads. They were then compelled to fall to the rear. I rallied them several times and … finally left out the stragglers.”

—Confederate officer Otho F. Strahl, 4th Tennessee Infantry, in his report on the Battle of Shiloh, April 1862

“We hurried down the hill again with orders to tear up the bridge, but when we got there a stream of fugitives hurrying across forbade our touching it, and we waited watching them. Here came a regiment of stragglers in disorderly haste, some hobbling with sore feet, some too lazy to move very fast in other circumstances, and some loaded with too many traps. Among the last was a gray-haired sergeant of the Irish Brigade … and the cause of his straggling made evident by a woman and child—his wife and child, probably—whom he guarded. It seemed a cruel time for them.”

— Second Lieutenant Thomas Livermore, 5th New Hampshire Infantry, on scene he witnessed during Seven Days Battles, in his diary

“The fact was, I was the youngest soldier in the brigade, and I looked it, so however harshly men talked to me they were really sorry for me, and I took advantage of it. There was one thing about my straggling: after I got my marching legs it was usually ahead of the regiment, not behind it. Gen. Pope issued an order for the commanding officer to march behind his regiment, to prevent straggling. That would not have bothered me. I always wanted to march way at the head of the corps if it was a corps movement, or of the division, or of the brigade. So when it was only my regiment moving I used to get so far ahead that Lt. Col. Baldwin, then in command, once made me carry a log of wood on my shoulder as a handicap.”

—C.W. Bardeen, a 15-year-old fifer in 1st Massachusetts Infantry, in his diary, February 1863

“That night and the next day we marched towards Washington and received news that General McClellan had been put in command again. The effect was like magic on the whole army. Men who had been straggling along, blue and dispirited, fell into place in their ranks with new vigor and new life, and with renewed determination and courage.”

—Stephen M. Weld, 18th Massachusetts Infantry, on his and his comrades’ learning, during their retreat after the Second Battle of Bull Run on the night of August 30, 1862, that George B. McClellan had been appointed to command the defenses of Washington, D.C., in his reminiscences of the war

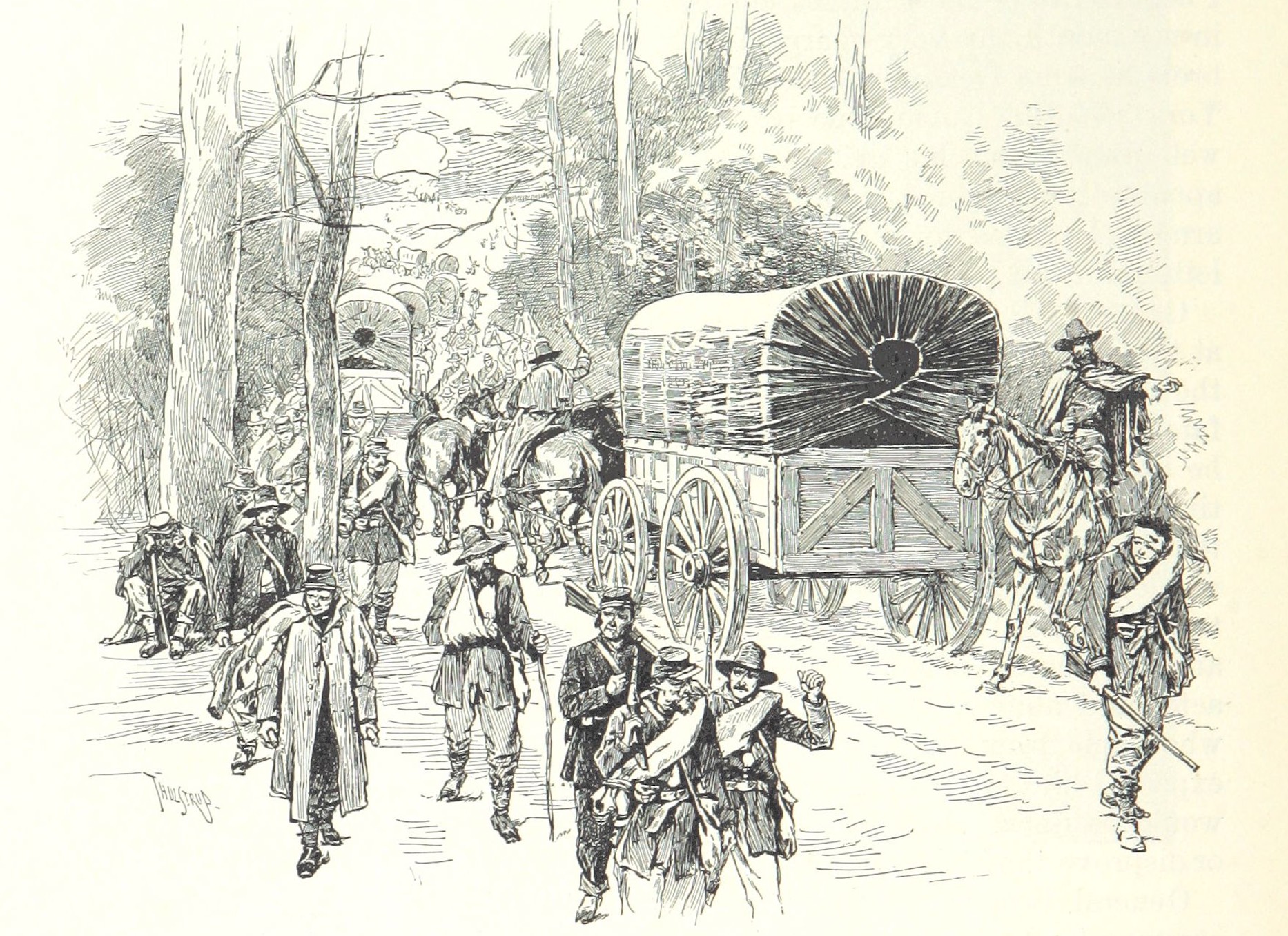

Stragglers join wounded soldiers on their march toward the rear of the army.

“Upon the discovery that they had disappeared, our brigade pursued, … taking up a goodly number of stragglers—the meanest in appearance that we have ever encountered yet, being the lowest scum of the Yankee foreign population. It was really a source of congratulation and encouragement to see that they were reduced to such straits for filling their ranks. One good soldier, I know, must be equal to ten such specimens of the genus homo. Not one in twenty of those we captured were natives of the United States.”

—Colonel Bryan Grimes, 4th North Carolina Infantry, in a letter to a former officer in the regiment, December 6, 1863

“It is outrageous how some of our straggling soldiery behave; entering and plundering houses of such things as are not needed to support the army, although orders against it are positive and severe, and which an honorable soldier, even when foraging would not dare to touch.”

—Colonel Oscar Jackson, 63rd Ohio Infantry, on the conduct of some Union troops during the March to the Sea, in his diary, December 2, 1864.

“[We were] ordered … [to] halt, and selecting the best ground that could be found, made preparations for camping…. In a few hours, all the stragglers in the rear came up, and were regaled and revived with strong coffee and food prepared by those who came in with the advance. A number of men, more vigorous or ambitious than the rest, did not halt at the camp, passing into the town and quartering themselves upon the inhabitants, and at hotels and groggeries. This breach of discipline and orders greatly displeased … [the colonel], and he at once took measures to secure the prompt return of this class of stragglers.”

—John C. Myers, 192nd Pennsylvania Infantry, on his regiment’s move to Gallipolis, Ohio, where they were to be stationed, in his diary, August 21, 1864

“The rumor is afloat that Joe Johnston is coming up in our rear. It had the effect of closing up a lot of miserable stragglers.”

—Union soldier Seth J. Wells, on the impact of the reported approach of Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederates during the Siege of Vicksburg, in his diary, May 24, 1863

“[H]ow unlike this day to any that have preceded it in my once quiet home. I had watched all night, and the dawn found me watching for the moving of the soldiery that was encamped about us. Oh, how I dreaded those that were to pass, as I supposed they would straggle and complete the ruin that the others had commenced, for I had been repeatedly told that they would burn everything as they passed.”

—Georgia resident Dolly Lunt Burge, on her fears of the passing Union army during the March to the Sea, in her journal, November 20, 1864

“[I]t would amuse you to see some of our big talkers, stragglers (members of Haversack’s Brigade, as we call them), … telling them all sorts of frightful yarns.”

—Mason Whiting Tyler, 37th Massachusetts Infantry, on the conduct of some of his comrades in the presence of contraband slaves, in a letter to a friend, June 20, 1864

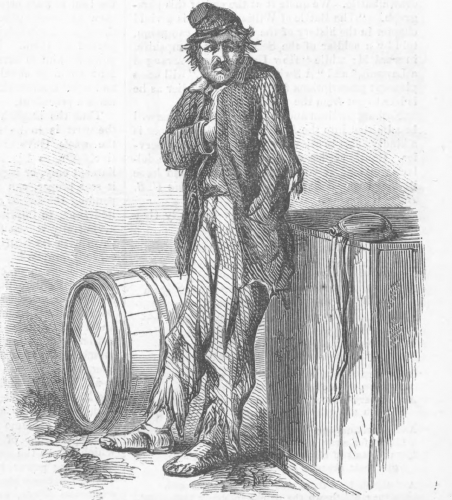

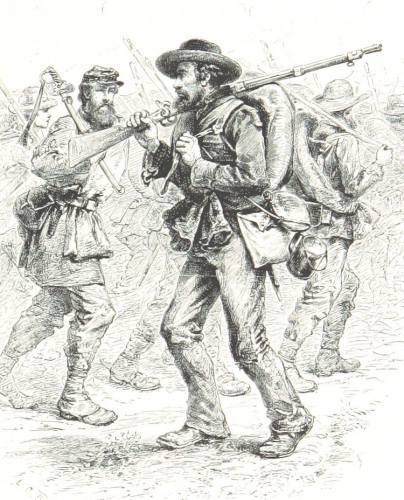

A Confederate straggler

“It was with much regret that we had to give up our post of honor as guard to the head of the army to take charge of sore-footed stragglers. But a soldier’s duty is to obey orders.”

—Luther Hopkins, 6th Virginia Cavalry, on an assignment he and his comrades received during the Maryland Campaign of 1862, in his memoirs

“Three days after the battle this corps numbered twelve thousand officers and men, though on the evening of the battle we could only muster seven thousand. Now, the difference of five thousand constituted the cowards, skulkers, men who leave the ground with the wounded and do not return for days, the stragglers on the march, and all such characters, which are to be found in every army, but never in so great a ratio as in this volunteer force of ours. I believe all that saves us is the fact that they are no better off on the other side, and it is well known that on the 17th instant the roads to Winchester on the one side, and Hagerstown and Frederick on the other, were filled with men who turned their backs on their respective commands engaged in fighting. It is, from all I can learn, about as bad on one side as the other.”

—Union general George G. Meade, in a letter to his wife about the Battle of Antietam, October 5, 1862

“The coffee ration was most heartily appreciated by the soldier. When tired and foot-sore, he would drop out of the marching column, build his little camp-fire, cook his mess of coffee, take a nap behind the nearest shelter, and, when he woke, hurry on to overtake his company. Such men were sometimes called stragglers; but it could, obviously, have no offensive meaning when applied to them.”

—Massachusetts artillerist John D. Billings, in his memoir of the conflict

“When we left Washington our men seemed to have forgotten all discipline. They ran out of the ranks everywhere to get water, or fruit, or to visit a house and I was constantly vexed and tired. I began to reform it, to keep up stragglers, to admonish, scold and punish, and to require all to do their duty. The work was hard, but encouraging in results, and we now get on passably well, better, I think, than any other Regt. of our brigade.”

—Lieutenant Colonel Willoughby Babcock, 75th New York Infantry, in a letter from 1864

“Between two and three thousand men were straggling along the road, unable to keep pace with the line, and in some cases whole companies left the line and filed into the adjacent woods to rest, and wait for the cool hours of evening to resume their terrible march. The line at last halted on the road, within eight miles of Richmond.”

—George H. Allen, 4th Rhode Island Infantry, on the effect of scorching summer heat on marching soldiers during the Peninsula Campaign, in a letter dated July 3, 1862

Union general Francis Barlow

“We kept on, on the flank of the column, admiring its excellent marching, a result partly due to the good spirits of the men, partly to the terror in which stragglers stand of Barlow. His provost guard is a study. They follow the column, with their bayonets fixed, and drive up the loiterers, with small ceremony. Of course their tempers do not improve with heat and hard marching. There was one thin, hard-featured fellow who was a perfect scourge. ‘Blank you! you–’ (here insert any profane and extremely abusive expression, varied to suit the peculiar case) ‘get up, will you? By blank, I’ll kill you if you don’t go on, double-quick!’ And he looked so much like carrying out his threat that the hitherto utterly prostrate party would skip like the young lamb. Occasionally you would see a fellow awaiting the charge with an air of calm superiority, and, when the guard approached, pull out … a ‘surgeon’s pass.’”

—Union staff officer Theodore Lyman, on the attention Brigadier General Francis Barlow paid to stragglers on the march, in a letter to his wife, June 13, 1864

“On this and subsequent marches frequent halts were made, to enable stragglers to close up; and I set the example to mounted officers of riding to the rear of the column, to encourage the weary by relieving them of their arms, and occasionally giving a footsore fellow a cast on my horse. The men appreciated this care and attention, followed advice as to the fitting of their shoes, cold bathing of feet, and healing of abrasions, and soon held it a disgrace to fall out of ranks. Before a month had passed the brigade learned how to march, and … covered long distances without leaving a straggler behind.”

—Confederate general Richard Taylor, in his memoir of the conflict

“The Yankees are about twelve miles from us and it was supposed that they would make an attack at this point, is the reason we were in such a hurry to get here that night. We would have made a very poor stand if they had. I don’t suppose we had more than one third of the men when we arrived here that night, when we came through Richmond. I had a very good opportunity of judging as our company was detailed that day as a war guard of the Brigade, to prevent straggling, and I marched behind with them for company. It’s no use trying to make a broken down man get up and march.”

—North Carolina soldier Walter Battle, in a letter to his mother, August 23, 1862

“I learned that one of the Pennsylvania Reserve regiments had been ordered to report to me for duty. Next day arrived 14 officers and 45 men only, with the news that the remaining 300 had refused to obey orders. The next day, however, they came straggling into camp in great disorder, and insolent. I at once gave them to understand that such conduct might pass where they came from, but not here, inasmuch as I happened to command.”

—Union general Alexander Hays, in a letter to his wife, February 17, 1863

“[T]he public, North or South, has never known how small was the force with which General Lee fought that battle…. The exhaustion of our men in the battles around Richmond, the subsequent battles near Manassas, and on the march to Maryland, when they were for days without anything to eat except green corn, was so great that the straggling was frightful before we crossed the Potomac.”

—Confederate general Jubal Early, reflecting on Confederate strength during the Battle of Antietam, in his memoir of the war