[F]ollowing his successful campaign to capture Atlanta in September 1864, William T. Sherman set his sights on Savannah. On November 15, Sherman’s force of approximately 62,000 men cut free from its supply lines and marched eastward in two massive columns, which remained 20 to 40 miles apart. A week later, Union troops reached and sacked the state capital at Milledgeville. From there, Sherman’s men continued their drive to the Atlantic Ocean, easily sweeping aside the small force of Confederate cavalry and militia left to contest their progress in a series of skirmishes and ravaging the Georgia countryside along the way. They tore up railroad tracks (heating and warping the rails into what the men called “Sherman’s neckties”), burned Confederate supplies, and foraged liberally at the expense of local civilians.

Union forces secured Savannah on December 21. The following day, Sherman sent President Lincoln a telegram: “I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, and also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton.” Over the course of the 26-day march, Union troops had inflicted an estimated $100 million in financial damages, as well as a brutal psychological toll on the state’s residents. Below is a visual overview of Sherman’s March to the Sea, many of the images produced at the time of the campaign.

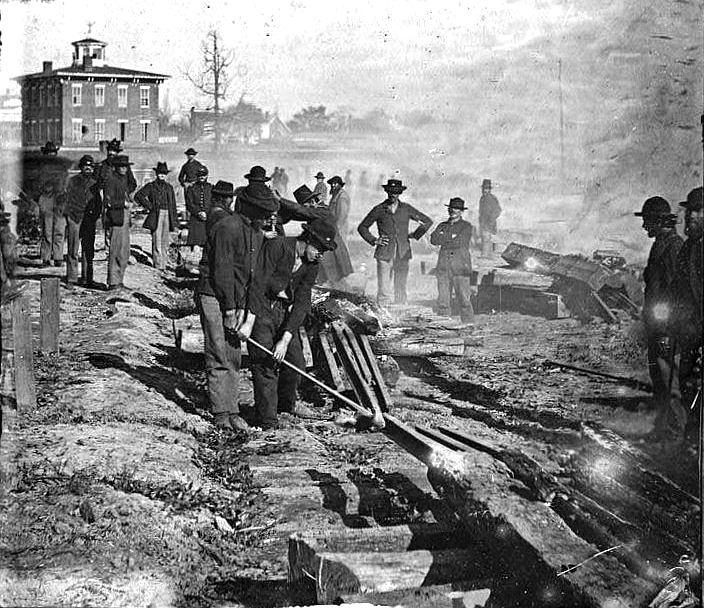

Sherman’s men tear up railroad track in Atlanta after capturing the city. (Library of Congress)

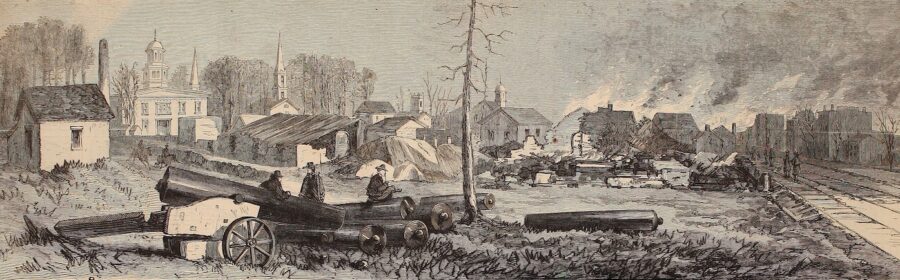

Union soldiers—part of Sherman’s force that took the city—look on as Atlanta burns in the distance. (Harper’s Weekly)

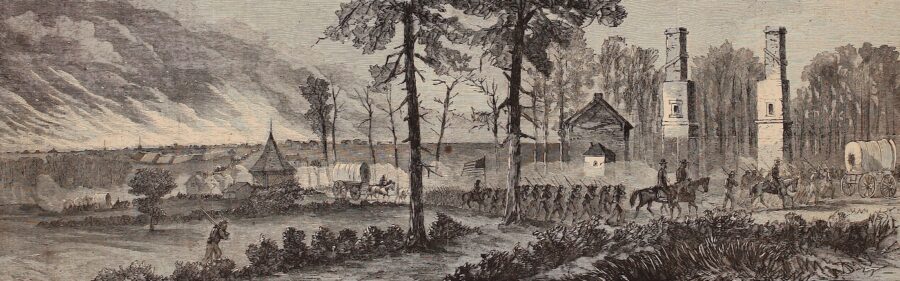

The men of the XIV and XX Corps—the left wing of Sherman’s army—move out of Atlanta on November 15, 1864, marking the start of the March to the Sea. (Harper’s Weekly)

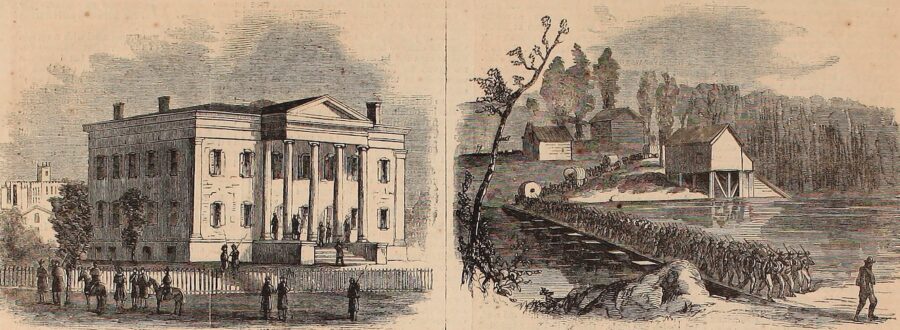

Sherman’s troops met only minor resistance during the campaign’s first days. On November 23, soldiers of Sherman’s left wing occupied the state capital at Milledgeville, which prompted the speedy departure of the governor and the state legislature. Above are shown the governor’s mansion in Milledgeville (left) and troops of the XX Corps crossing Little River near the city. (Harper’s Weekly)

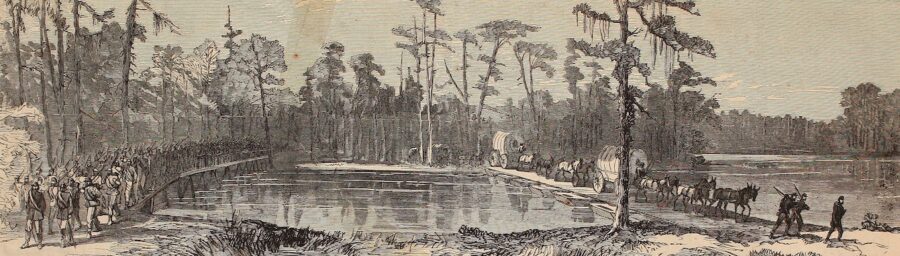

As Sherman’s left wing advanced toward Sandersville, the right wing encountered resistance on November 25 at the Oconee River, over which men of the XVII Corps had erected a pontoon bridge. The resistance was light and only slightly delayed the continued advance. (Harper’s Weekly)

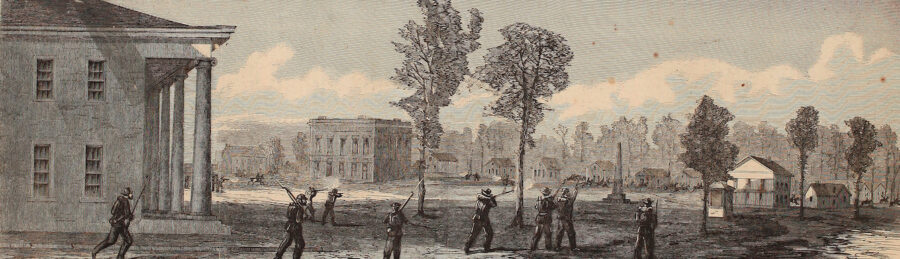

On November 25–26, troops of the left wing clashed with Confederate cavalry commanded by Joseph Wheeler at Sandersville (shown above). Roughly a week later, Union horsemen would soundly defeat Wheeler’s men at the Battle of Waynesboro. (Harper’s Weekly)

As they moved toward Savannah, Sherman’s men tore up railroad track, destroyed cotton gins and mills, confiscated millions of pounds of corn and fodder, and siezed thousands of horses, mules, and heads of cattle. Above: Union soldiers destroy railroad tracks and telegraph poles and burn buildings in this 1868 depiction of the March to the Sea by artist F.O.C. Darley. (Library of Congress)

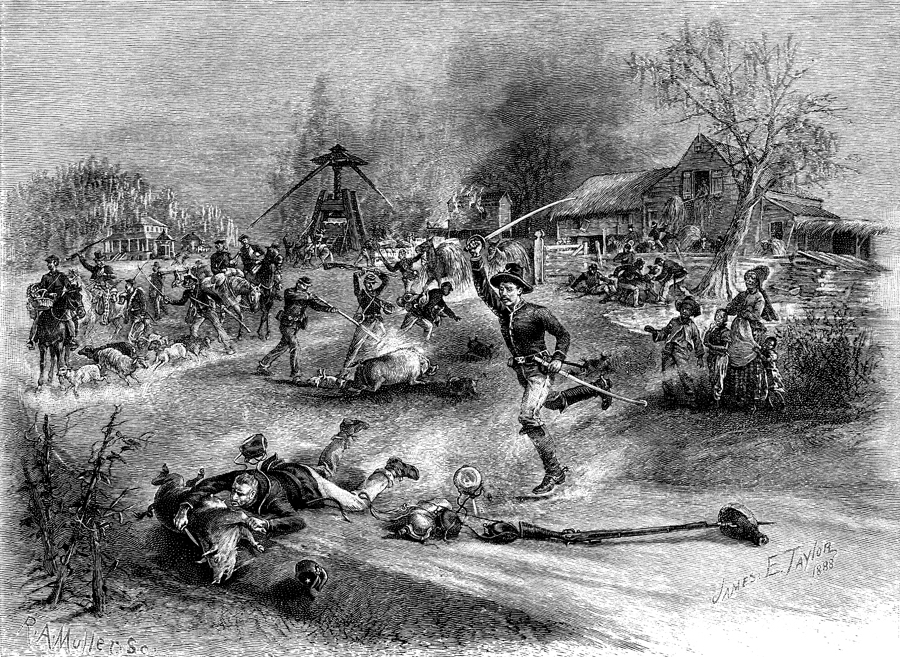

The foragers in Sherman’s army—known as “bummers”—earned an especially notorious reputation during the campaign. As the main columns marched, the bummers spread out for miles in either direction to look for food, livestock, and other valuables. And while Sherman had issued orders at the start of the campaign that “Soldiers must not enter the dwellings of the inhabitants, or commit any trespass,” he later acknowledged, “No doubt many acts of pillage, robbery, and violence were committed by these parties of foragers….” (Battles and Leaders of the Civil War)

On December 10, when Sherman approached the outskirts of Savannah, his men encountered 10,000 entrenched Confederates commanded by William J. Hardee. Union batteries soon engaged with Confederate gunboats on the Savannah River, including the ship Resolute, shown above. (Harper’s Weekly)

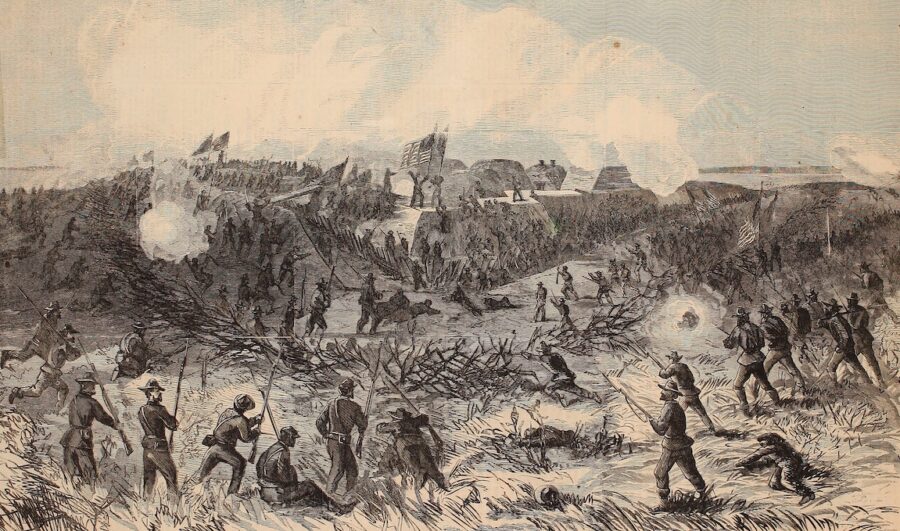

Three days later, soldiers from the XV Corps stormed Fort McAllister, the formidable Confederate bastion that guarded Savannah, and captured it within 15 minutes (depicted above). The victory allowed Sherman to link up with his supply line—a fleet of Union ships just off the coast of Savannah commanded by Admiral John Dahlgren. (Harper’s Weekly)

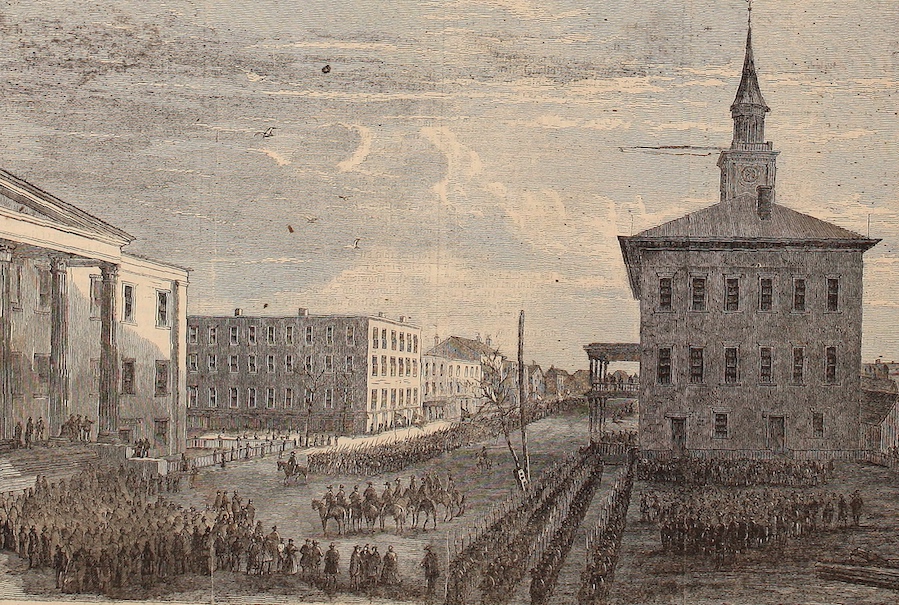

On December 17, a confident Sherman sent a message to Hardee in the city. “I have already received guns that can cast heavy and destructive shot as far as the heart of your city; also, I have for some days held and controlled every avenue by which the people and garrison of Savannah can be supplied, and I am therefore justified in demanding the surrender of the city of Savannah, and its dependent forts, and shall wait a reasonable time for your answer, before opening with heavy ordnance….” Instead of surrendering, Hardee and his men escaped on December 20 via a pontoon bridge on the Savannah River. The next morning, Savannah’s mayor rode out to Union lines to surrender the city; Sherman’s men marched in (shown above) and occupied it the same day.

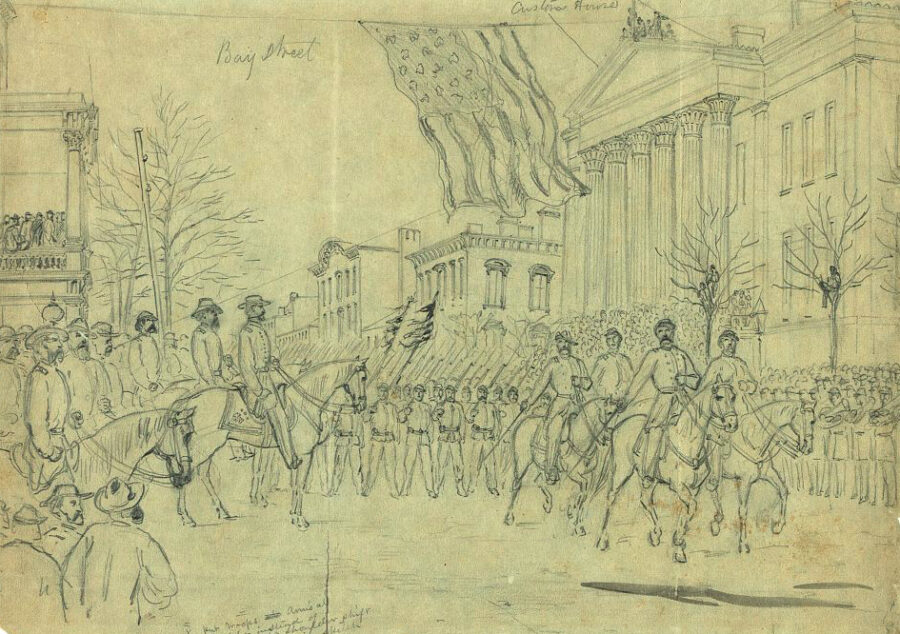

Above: Sherman reviews his army in the streets of Savannah before launching his next campaign northward into the Carolinas. While Sherman’s March was—and is—often credited with helping to end the Civil War by undercutting the Confederacy’s ability to sustain the conflict, controversies linger. In the aftermath of the campaign, southerners alleged that Sherman’s men had gone out of their way to abuse civilians—including women and children. Even in the North, some observers were outraged when Sherman defended the actions of one of his generals, Jefferson C. Davis, at Ebenezer Creek. On December 9, Davis ordered a pontoon bridge pulled up before hundreds of escaped slaves, who had been following the Union army in search of safety, could cross. Stuck between the river and approaching Confederate cavalry, many dove in desperation into the icy cold water, only to drown while trying to make it to the opposite shore. (Library of Congress)