Spoiler Alert: This article, which appears in the Fall 2017 issue of The Civil War Monitor, will discuss major plot points in the 2017 film The Beguiled.

The Beguiled may not seem, at first, to be a Civil War film. The movie, which is a remake of the 1971 Clint Eastwood feature (which was itself based on the novel A Painted Devil by Thomas Cullinan, published in 1966), begins with a panning shot of treetops and the sound of birdsong and buzzing insects. As the camera comes to the ground, it follows a young girl named Amy (Oona Laurence), humming to herself as she picks wild mushrooms. As she walks down a long avenue of live oak trees festooned with strands of Spanish moss, there is a faint cannon boom in the distance. Amy pays this no mind. The sounds of war are common in this part of 1864 Virginia, just another of life’s reverberations.

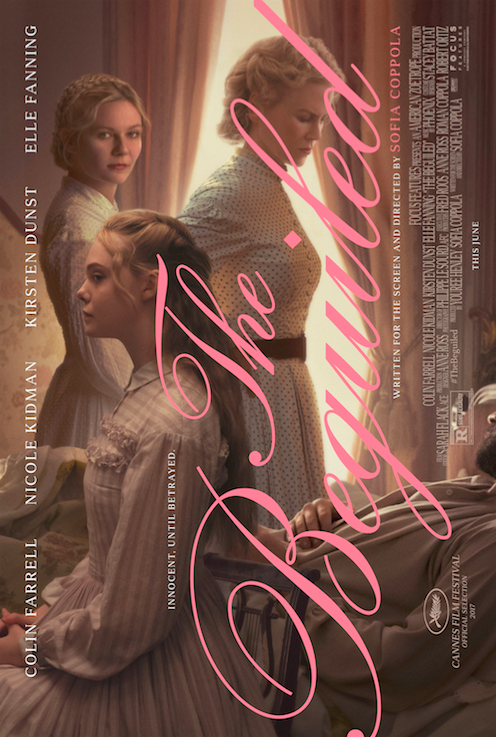

Amy happens upon a wounded Union soldier (Colin Farrell). They exchange names and pleasantries, and then Amy escorts the soldier—a corporal in the 66th New York Infantry named John McBurney—to the grounds of the Farnsworth Seminary for Young Ladies, where he passes out from blood loss. Amy summons her fellow students, her teacher Miss Edwina (Kirsten Dunst), and the headmistress, Miss Martha (Nicole Kidman), to help carry him inside.

The entrance of a strange northern man into these southern women’s domestic space changes all of their lives. It is a pivotal moment in which the battlefield and the home front collide—a wartime experience that has been the subject of several recent Civil War histories.

Over the course of the war, as Confederate and Union forces maneuvered back and forth over the southern landscape, female-led households took in the injured and the dying from both armies. Northern men entered southern homes in other, more violent ways as well.

Actress Kirsten Dunst (left) and screenwriter and director Sofia Coppola on the set of The Beguiled

As historian Lisa Tendrich Frank argues in The Civilian War: Confederate Women and Union Soldiers during Sherman’s March (2015), Union officers including William Tecumseh Sherman recognized the power that southern women had in sustaining the Confederate war effort—and targeted them in order to undermine that power. Union soldiers knocked down doors, entered parlors and bedrooms, and rifled through bureaus, “besieging the female domain” in order to humiliate and dominate southern women.

That Sofia Coppola’s film should reflect studies in Civil War gender history is probably an accident. She is not particularly interested in the historical reality of the war, especially its roots in slavery and emancipation. This is evidenced by the fact that she removed Mattie, the only enslaved woman in the novel and the 1971 film, from her production, a choice for which she has been much criticized by historians. In order to explain the distinctive whiteness of Farnsworth, Amy tells McBurney that “the slaves all left.” McBurney accepts this explanation, and does not bring it up again. That he is an Irish immigrant, a bounty soldier, and possibly a coward also serves to prevent conversations about slavery that a Union soldier might otherwise have had with southern white women.

These elements of plot and characterization allow Coppola to (mostly) ignore history and focus instead on the southern gothic vibe of Farnsworth and the interpersonal, psychosexual dynamics that McBurney’s arrival catalyzes. “You can trust me in your place, ma’am,” he reassures Miss Martha. But we know not to trust the sly look in his big brown eyes.

Almost immediately, McBurney inaugurates a campaign of his own, assessing the needs and desires of the Farnsworth women and manipulating them accordingly. Standing at a window with the shy Edwina, he raves about her beauty and independent spirit. Sipping brandy with Miss Martha, McBurney compliments her strength as the head of household. He tells Amy, his savior, that she is his “best friend” in the house, that he relies on her for everything. He does not have to work hard to woo Alicia (Elle Fanning), the petulant teenager; she makes eyes at him from the beginning. Through all of his flirting, McBurney makes the Farnsworth women believe that although they saved his life, it is he who has rescued them from the tedium of daily wartime survival. And they love him for it.

The mood in the house changes, however, when McBurney sneaks away from his makeshift room in the parlor and makes his way upstairs to Alicia’s bedroom. This is a profound breach of etiquette, an invasion of the women’s privacy. When Edwina discovers his treachery, she shoves him down the stairs and a bone in his leg snaps. The women panic and drag him back into his parlor room, blood staining their snowy white nightdresses. It is a scene reminiscent of Gone With the Wind, when Scarlett shoots the Union straggler on his way up the stairs of Tara, and Melanie offers her nightgown as a shroud.

Nicole Kidman as Miss Martha and Colin Farrell as Union soldier John McBurney in a scene from The Beguiled

Back in the Farnsworth parlor, Miss Martha amputates McBurney’s leg. That she accomplishes it without killing McBurney is perhaps the most remarkable flight of fancy in the entire film. This is another pivotal moment, when The Beguiled’s quietness turns to menace and Civil War gender history comes back into play. McBurney awakens to a missing leg and loses his mind. He rants and raves, throws furniture around the parlor, and accuses the “vengeful bitches” of Farnsworth House of taking his leg on purpose.

Historians of Civil War wounding and disability—such as Brian Craig Miller, author of Empty Sleeves: Amputation in the Civil War South (2015)—will recognize this McBurney, the man who equates the strength and wholeness of his body with his manhood. “I’d rather be dead than a man without a leg,” he shouts at Miss Martha and the girls. “I’m not even a man anymore. You butchered me!”

At this point the danger that McBurney embodies from the beginning of the film comes to fruition. He gets ahold of Miss Martha’s revolver, and threatens to kill them all. “We are not safe with him in the house,” Miss Martha concludes. This sets in motion another campaign, one that the Farnsworth women wage against the Union soldier who has invaded their home.

That they rid themselves of McBurney at the dinner table, making polite conversation and wearing their best clothes and jewelry, is part of their reassertion of female power. They use their sewing skills to seal his corpse into a bed sheet before they carry it out of the house, just as they carried his wounded body in.

The film’s quietness returns in the final scene, as the Farnsworth women wait on the porch for Confederate soldiers to arrive and take McBurney’s body away. The camera recedes slowly, putting the Farnsworth gate between the audience and the women. They have survived the invasion of their home, and in doing so have created their own, sequestered community of violence. It appears, then, The Beguiled is a true Civil War film after all.

Megan Kate Nelson is a writer and historian who lives in Lincoln, Massachusetts. She is author of Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War (2012) and Trembling Earth: A Cultural History of the Okefenokee Swamp (2005).