In June 1865, Jim Jackson—one of Missouri’s more notorious Confederate guerrilla commanders—made haste for the Illinois line. The Confederate experiment to which Jackson belonged had recently ended in disaster. On the regular front, roughly two months before the former guerrilla started his northwestern trek, Robert E. Lee had surrendered the tattered remains of the Army of Northern Virginia. And on the irregular front, even Missouri’s pro-Confederate contingent had begun the process of rebuilding a domestic environ shattered by guerrilla violence and what historians, such as Joseph Beilein, have dubbed “household war.” Thus Jackson’s attempted exit from the state wasn’t particularly surprising; he’d terrorized Unionists in Missouri’s northern and western sectors for much of the war and, as a result, his victims weren’t likely to forgive or forget on account of a peace negotiated in the Eastern Theater.

With this in mind, it’s also not surprising that Jim Jackson never made it out of Missouri alive.

The details of his death vary slightly from source to source, but one fact—that Unionists took Jackson’s life after the war had “officially” ended—is irrefutable. Near the beginning of Jackson’s journey to Illinois, a group of men overtook him and another ex-guerrilla, William Farley, in Pike County, Missouri. Ironically, the men were actually on the hunt for another man and seemingly stumbled across Jackson. According to some reports, Jackson’s captors were a group of civilian farmers, one of whom accused him of wartime thievery and murder, before turning him over to a Union militia company; in other accounts, though, the men who initially overtook Jackson and Farley are a band of militiamen from Audrain County, Missouri. In any event, once in Union custody Jackson was found guilty of both aforementioned crimes, taken to Monroe County (for reasons never fully explained by anyone), and then executed there by the Audrain militiamen. Renditions of the story even differ as to how Jackson was killed: some claim that he was hanged, others that he was simply shot in the head.

In meeting such a violent end, Jackson was not unlike many of his wartime contemporaries. In 1864, William “Bloody Bill” Anderson died while attempting to charge an entire line of fortified federal troopers in Ray County, Missouri—troopers who had been trained and dispatched specifically to exterminate the guerrilla captain by whatever means necessary. In 1865, William Clarke Quantrill met a similar fate. By then, Anderson and other aspiring guerrilla leaders—many of whom had been Quantrill’s former lieutenants—had pushed the architect of the 1863 Lawrence Massacre out of Western Missouri. While operating on a smaller scale in Kentucky, Quantrill was tracked down and shot by Union guerrilla hunter Edward Terrill. And in 1866, Archibald “Little Archie” Clements, likely a true sociopath and the man who took over Anderson’s command, was killed in the midst of a running gun battle in Lexington, Missouri. Clement refused to surrender to Union authorities and, according to local lore, after sustaining multiple wounds and a broken arm, he died attempting to cock a revolver with his teeth.

But Jim Jackson’s death was also quite different from those of Anderson, Quantrill, and Clement in one major respect: Jackson had voluntarily surrendered and taken the Oath of Loyalty before Unionists caught up with him in Pike County. Around 11 a.m. on June 13, 1865, donning a flashy guerrilla shirt, Jackson rode into Camp Switzer under a white flag with several of his men in tow. Here, at the Union post near Columbia, Missouri, they gave themselves up to Captain H. N. Cook and swore allegiance to the government of the United States. The wording of loyalty oaths could change slightly from state to state or district to district, but they typically went something like as follows:

I ____________________ do solemnly swear (or affirm) in presence of Almighty God, that I will henceforth faithfully defend the Constitution of the United States and the Union of the States thereunder, and that I will in like manner abide by and faithfully support all laws and proclamations which have been made during the existing rebellion, with reference to the emancipation of slaves, so help me God.

The other men who took the oath were William Stephens, William Farley, John West, Barton Ramsey, William Hill, James Mayfield, Samuel Nunnelly, Joel Ramsey, Samuel Rowland, George Spears, Madison Evans, William McCarty, Abraham Rumans, John Mullen, and William Martin. In doing so, as noted by the June 23, 1865, edition of the Missouri Statesman, all had been “granted a parole under President Johnson’s amnesty.” As official parolees, each man was allowed to return home, now—at least in theory—a normal member of society.

So what drove Union militiamen to ignore this protocol and dispatch Jim Jackson just a week or so later? To answer this question, we need to start from the beginning of his irregular career. In the early years of the Missouri-Kansas guerrilla theater, Jackson first fought under another infamous partisan, Clifton Holtzclaw. Possibly owing to his antebellum stint as a Texas Ranger, Jackson rose through the guerrilla ranks quickly and eventually formed his own company of bushwhackers. As a leader, two things stood out about Jackson’s record and made him a serious thorn in the sides of both Union civilians and federal authorities in the Border West.

First, in October 1864, as Confederate General Sterling Price tried to invade and “retake” Missouri, Jackson was employed to create a distraction. He led an unprecedented guerrilla raid into neighboring Iowa. (Several other guerrilla commands were also enlisted for the same purpose—though most operated in Missouri and none but Jackson ventured into Iowa.) In what historian Daniel Sutherland describes as a “twelve-hour spree” that “rocked the state,” Jackson and about a dozen of his guerrillas gunned down at least three men, put several houses to the torch, and took multiple hostages (who were later released alive).

Second, Jackson was well-known for brutality among white and black Unionists in Missouri—but he especially hated the state’s population of African American freedmen. According to one source, “he and his gang took special delight in persecuting new Black freedmen or any white person who sought to hire them.” In one instance, in February 1865, “Jackson and his boys visited the home of Dr. John W. Jacobs in eastern Boone County and proceeded to ‘string-up’ one of his hired Blacks. They issued threats of similar treatment to other nearby farmers who would hire the freedmen.” In still another, Jackson personally informed a farmer in Ralls County, Missouri, that “my garrilis is heard that you have a couple of famallely of negros that settle on your plase… If you dont make dam negroes leve there ride away I will hang the last negro on the plase and you will fair wors for we cant stand the dutch and negros both.”

On one hand, it becomes clear that Unionists in Missouri didn’t believe they could or would be safe—even with the war supposedly over—while Jackson still roamed the backwoods and lonely roads of any nearby county. And even as he claimed to be leaving for Illinois at the time of his capture, there was no guarantee that the guerrilla wouldn’t come back with torch and revolver at the ready. On the other hand, from the perspective of military officials who would’ve overseen or, at the very least, been capable of staying Jackson’s execution, he was a dual threat to law and order in Missouri and in neighboring states. During the war, Jackson had helped Missouri’s irregular conflict spill over into Iowa, a state with no significant secession movement. Therefore it’s fairly logical to assume that the Audrain County militia didn’t want Jackson hanging around their home territory based on his standard wartime exploits—but because of his 1864 antics in Iowa, nor did they think he was safe to set loose upon Illinois, whether he’d sworn to behave himself or not.

Unionists in Pike County and the Audrain militiamen made what probably seemed to be the only decision that could guarantee the long-term safety of their homes moving forward. They captured and killed Jim Jackson without a formal trial, military or civilian. Despite his wartime record and penchant for violent white supremacy, it is an unavoidable fact that Jackson had been officially paroled by a captain of the federal army after formally surrendering himself and completing all required loyalty procedures. Therein, for better or worse, Jim Jackson was essentially the victim of a state-sanctioned murder in June 1865.

But Jackson’s situation wasn’t altogether unique in Missouri. Other ex-guerrillas were also targeted by government or military officials. For example, in a letter dated March 19, 1866, Governor Thomas Clement Fletcher plotted to have Jim Anderson, a former guerrilla (and brother of “Bloody Bill”) assassinated. “I am told that Jim Anderson & his men are about Franklin Howard County,” Fletcher wrote, continuing that “if they can be captured or killed it would be the best thing for the state I know of.” Several years later in 1882, another governor of Missouri, Thomas T. Crittenden, brokered a deal with the Ford brothers, Charlie and Bob, to assassinate ex-bushwhacker Jesse James in exchange for criminal immunity. On April 3, 1882, the deal was completed when Bob Ford shot James in the back of the head at the outlaw’s home in St. Joseph, Missouri.

The main difference between Jackson’s case and those of Anderson or James, though, is that both of the latter had developed into well-known postbellum bandits. For his part, Jackson had only managed to rob a single stagecoach on April 29, 1865—before the war in Missouri was even definitively over—and hadn’t posed an immediate threat to the banks or railroads who had pressured Crittenden to terminate men like Jesse James.

In other words, it was his wartime record as a guerrilla commander that had sealed Jackson’s post-war fate—harsh consequences from which the likes of Quantrill and Anderson had been excused by death. As a bane to many Unionist civilians during the war, Jackson garnered no postbellum sympathy and, as his lesser-known men faded back into obscurity, he was left with few friends in the state. In 1863-64, Thomas Ewing’s General Order #11 and other harsh Provost measures had virtually eliminated the ability of pro-Confederate households and kinship networks to support guerrilla warfare on an effective scale. In turn, Jackson lost not only his wartime calling, but also the lifestyle and mode of violence that would have probably afforded him the best means of self-protection when vengeance-seeking Unionists came calling.

So again, we return to the question of why Jim Jackson was killed when so many other guerrillas melted back into the fabric of everyday life in postbellum Missouri?

The most pragmatic answer is that the fundamental nature of guerrilla warfare in the Border West simply caught up with him. As a bushwhacker, he’d bet all of his chips on a successful irregular insurgency in Missouri. Put another way, Jackson had waged war without regard for the consequences that would accompany a losing effort. He’d harassed neighbors and former acquaintances, he’d terrorized entire communities, and he had not done these things as an anonymous soldier or one of thousands marching through a particular locale. As with the case of the Ralls County farmer, Jackson announced his grim intentions. He thrived on an intimate brand of warfare in which his targets often knew who was coming to kill them or in which Jackson left calling cards after-the-fact.

In this way, Jackson revealed the double-edge of fame in the guerrilla theater. He exploited and enjoyed his notoriety, to be sure—his reputation for terror bolstered his ability to disrupt and damage federal operations and support. But this ill-repute also came with a steep price: post-war anonymity became a complete impossibility. Such a flamboyant, personalized campaign of violence also required that Jackson’s would-be victims adopted similar tactics for sake of survival during the war. Irregular warfare was very capable of breeding shortsightedness; as such, none of this was a major concern for the guerrilla while things were going his way.

Then things stopped going his way. The tables began to turn in favor of Unionism and the Confederates lost the irregular war in Missouri. Guerrilla leaders started dying and most of their men understood that the time for flashy guerrilla shirts and bold statements was over. For Jackson personally, without a full-scale guerrilla movement functioning around him, his personal brand of warfare now made him one of the most vulnerable men in the state. Farmers looking to settle a score or fulfill a feud may not have remembered all of Jackson’s men—but as mentioned above, they sure as hell remembered Jim Jackson.

So in a war fought almost entirely on the homefront—a war in which occupying forces and combatants didn’t simply break camp and go home at fight’s end—it appears that Jim Jackson re-learned a lesson about mortality and irregular violence that he, himself, had imparted so many times to others. It’s more than a little ironic, then, that we don’t know which material, rope or lead, ultimately ended Jackson’s life. Because as the guerrilla had used his fair share of each to send macabre messages about emancipation and Unionism to his enemies in Missouri, those same men replied to Jackson in kind in June 1865: no peace settlement, no oaths of loyalty, no promises of exile in Illinois, and certainly no parole papers could finish the sort of fight that Jackson had started. This was a winner-take-all bout to the death and no band of followers would be materializing from the brush to save him this time.

Interestingly enough, if Kansas City’s Daily Journal of Commerce was more or less accurate in its reporting of June 29, 1865, Jackson apparently accepted that this was how things had to be by the time of his death:

Jackson and Farley were informed that they must die. The intelligence seemed to have but little effect upon them. Jackson remarked, ‘I want brave men to shoot me. If I must die, let it not be by the hand of a coward. I am a brave man myself, and let me be killed by one.’

Whether or not Jackson’s death was a murder, a lynching, a just execution, or some other act of vigilante justice is, in the end, up to you to decide for yourself. Factions in Missouri have been disagreeing about it for almost 150 years, after all. But just in case what the editors of the pro-Union Journal believed had motivated his executioners wasn’t clear to outsiders or to posterity, they contended plainly that the bushwhackers Jackson and Farley appropriately died “as many others had by their hands, unshriven of their sins.”

Matthew C. Hulbert is a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Georgia and the author of numerous articles on Civil War memory and guerrilla warfare in the western borderlands of Missouri and Kansas.

Sources: Joseph Beilein, Jr., “Household War: Guerrilla-Men, Rebel Women, and Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri,” Ph.D. Diss., University of Missouri, 2012; Joanne Chiles Eakin & Donald Hale, Branded as Rebels (Eakin & Hale, 1993); James Erwin, Guerrilla Hunters in Civil War Missouri (The History Press, 2013); Michael Fellman, Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the American Civil War (Oxford, 1989); Louis Gerteis, The Civil War in Missouri: A Military History (University of Missouri Press, 2012); History of Boone County, Missouri (Western Historical Company, 1882); Kansas City Daily Journal of Commerce; “1866 Letter from Governor Thomas C. Fletcher to Unnamed Union Colonel” (K0220), State Historical Society of Missouri, Kansas City, Missouri; “Oath of Allegiance from W. H. Prewitt Papers,” folder 217 of The Missouri Collection (C3982), State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia; T. J. Stiles, Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War (Vintage Books, 2003); Daniel Sutherland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2003); LeeAnn Whites, “Forty Shirts and a Wagonload of Wheat: Women, the Domestic Supply Line, and the Civil War on the Western Border,” Journal of the Civil War Era 1, No. 1 (March 2011).

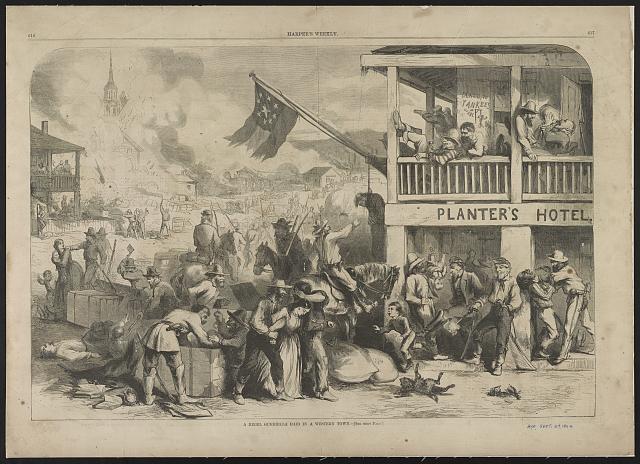

Illustration courtesty of the Library of Congress (loc.gov).