Undoubtedly, over the next few days newspapers and blogs will provide enthralling details about the Battle of Gettysburg on the 150th anniversaries of each of its three days. In our age of practically instantaneous news coverage, it might also prove interesting to examine what contemporaries learned as the battle actually unfolded.

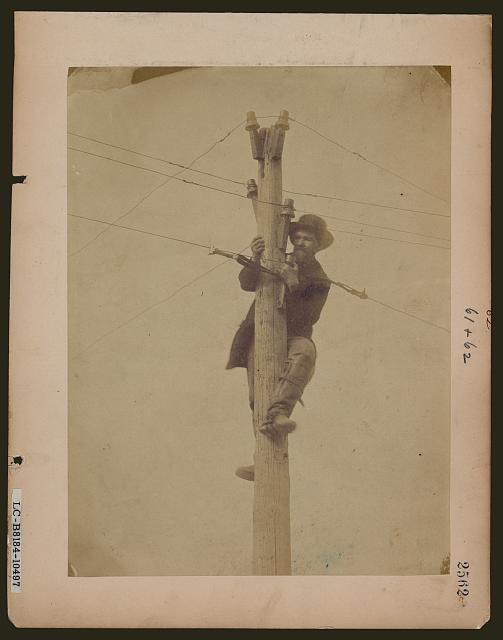

Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began crossing the Potomac River on June 15, 1863, and thanks to the telegraph, newspapers reported it only a day later. In those times, editors had little plagiaristic concern about printing articles from other papers. New York newspapers often had the most current information about Lee’s movements, but these reports were seen in papers all over the North and South.

Lee’s intentions were a mystery, but by June 20, reports arrived (many only a day old) from journalists scattered over Maryland and Pennsylvania. Clearly, the Rebels were feasting off the land. “His troops are doubtless now fed a hundredfold better than at any previous period of this year,” the New York Herald asserted. The Philadelphia Enquirer claimed the Rebels were “well clothed—much better than the citizens expected to see, were well armed, and in an excellent state of discipline.” Readers learned that citizens were securing valuables, hiding animals in the mountains, and frantically fleeing northward. The New York Times reported the particularly odious news that the Confederates were also grabbing “every black man, woman, and child, whom they could lay hands on. Everyone knows they have not carried them off as prisoners of war . . . but as chattels, to be sold into Slavery.”1

Editors speculated about Lee’s objective, but there was no consensus. “Reports of . . . heavy columns of Rebel infantry are plentiful and positive,” the New York Tribune asserted on June 26, “but not yet sufficiently exact.” Some believed Lee intended to capture Washington; others felt the target was Baltimore, or Philadelphia. The Tribune refused to speculate; “We prefer to leave [that] to Gen. Hooker,” they declared, referring to the soon-to-be-removed leader of the Army of the Potomac.2

Some news seemed humorous. The Pittsburgh Chronicle conversed with a Rebel who tapped into a telegraph line and pronounced that the Confederates would “thrash hell out of you damned Yankees yet.” When asked how many troops Lee had, the Rebel wisely exaggerated: “two hundred thousand, more or less.” Asked where they were going, he responded, “We’re going North, and will take charge of [everything] in a few days.” After more back-and-forth, the Chronicle noted, “the Rebel began to lose his temper, and became very abusive, using language which will not bear reporting.”3

By June 29, northern papers reported that the Federals were now also north of the river and that Lincoln had replaced Hooker with George Meade. Since the new commander was largely unknown to the public, papers provided his biography and assured that he was appropriately experienced. Military censors prevented journalists from revealing the Union army’s movements, but correspondents promised that the Army of the Potomac “will soon be heard from.”4

At the end of June the Confederate target increasingly appeared to be Harrisburg, so northern editors ordered correspondents to go there. Soon, as many as 20 papers had representatives in the city, and thus the most up-to-date dispatches came from Harrisburg. Unfortunately, this meant that Lee’s movements became murkier, especially when officers banned reporters from traveling south of the Susquehanna.

Without new solid news to report, editors turned to assigning blame. The New York papers faulted Pennsylvania for not organizing an effective defense. The Times asserted that had the Rebels invaded their state, New Yorkers “would [have] come down on the rebel attack like an avalanche!” Others blamed anti-war politicians like Fernando Wood (the New York congressmen memorably portrayed in Spielberg’s Lincoln). One widely circulated report claimed that the so-called “Copperheads” had put the invasion in motion. A “reliable source” claimed that one of the movement’s leaders had recommended to Confederate President Jefferson Davis “to march an army into Pennsylvania and lay waste her fields and burn her towns.” The report noted “the latter part of the suggestion was too barbarous a policy for even Jeff. Davis to adopt,” but he then ordered Lee’s invasion.5

Northern papers agreed that the situation was dire. The Rebel army, editors noted, was confident and enjoyed the initiative. Further, Meade was frighteningly new to command. The Chicago Times wondered if the nation was “as well prepared as we should be for possible disasters.” The New York Times warned that if Lee defeated Meade’s army, he could roam farther north. It was dangerously apathetic “to wait here in New-York, singing and dancing and buying and selling.” With the Rebels plundering small Pennsylvania towns, the Times wondered how much wealth would be lost if they made it to New York. “Let Wall-street figure [that] up,” the editors noted contemptuously.6

With reporters trapped in Harrisburg, desperate editors ordered their men in Washington out into the field. The papers had correspondents traveling with Union army, but they were out of contact because the Rebels had cut the telegraph wires. Reporters like the Cincinnati Gazette’s Whitelaw Reid and the New York Tribune’s Aaron Homer Byington frantically rode toward the gathering armies.

Americans were largely unaware when the battle began on July1. Several newspapers speculated that day that Lee’s failure to attack Harrisburg indicated that the invasion was merely a massive foraging expedition. Lee “certainly has not acted as though hungry for a fight,” the New York Tribune opined. “For, if he had wanted one, he could have easily have forced it.”7

However, that night correspondents in Harrisburg and Lancaster telegraphed interesting observations. “Signal rockets were seen, and firing heard last night in the direction of Gettysburg,” the Chicago Tribune printed on the morning of July 2, “and [it] continued until three o’clock this morning.” Additionally, people had heard “rapid and heavy” cannonading. This vague information was the first news reports about the battle.8

Later on July 2, The New York Times received the first news from the scene. Their man Lorenzo Crounse was headed toward Gettysburg, but was slowed by advancing columns of Union soldiers. Still, battle news trickled down the line with the men, and he gathered enough to get a broad picture of events. That evening he managed to get a telegram out and The New York Times printed his succinct dispatch in a late edition. Details were slim, but it reported a heavy fight west of Gettysburg on the Chamberburg Pike that lasted all day. The blows were heavy, but the Union army stood firm. “I regret to say,” Crounse added, “Major-Gen. Reynolds was mortally wounded and has since died.”9

On the morning of July 3, other northern newspapers printed this report, but the New York Tribune and the Philadelphia Press had more details. A. H. Byington had cajoled and paid a telegraph operator and workmen in Hanover to quickly repair their line. On the night of July 2, he got a message to New York via Washington. Having left the battlefield before the major events that day, his details were mostly about the first day’s battle. The War Department had heard nothing from the army, and unknown to Byington was eagerly listening to his late-night transmission. The president asked telegraphers to send the question, “Who is Byington?” The reporter responded by suggesting that they ask the secretary of the navy. Gideon Welles was then shaken out of a midnight slumber, and he vouched for the reporter’s credibility. The War Department asked Byinton to relinquish the line so they could contact the army, but he agreed only after extracting a promise to pass his transmission on to the New York Tribune and the Philadelphia Press.10

On July 3, many papers printed slim details borrowed from the Crounse and Byington reports. They indicated that on July 1 Rebels had forced the Federals back through the town, but late in the day, Union troops had formed on good high ground. Witnesses had seen Reynolds’ body arrive in Baltimore, confirming his death. Furthermore, the Union army was better concentrated than the Confederates appeared, both armies were now arriving en masse, and there was sure to be an epic clash on July 2. That was about it. Most of the war news that day concerned the cavalry battles that had taken place at the end of June. Thus, as the Battle of Gettysburg was reaching its dramatic climax on July 3, most northerners knew little more than a few details about the fighting on July 1. “The news from Pennsylvania is exciting,” the Chicago Tribune noted, “but somewhat meagre [sic].” Surely, this made for an anxious Friday afternoon.11

Yet during the night of the 3rd, repaired telegraph lines hummed with activity. Unlike Byington, most of the approximately 45 reporters on the field did not leave while the battle was raging, electing to see it out. Once it ended, they rushed to find working telegraphs, filling them with hurriedly written, but often eloquent, dispatches. Additionally, Meade had made contact with Washington the night before.

Thus on the 87th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, northerners awoke to exhilarating news. “The Victory Undoubtedly Ours,” the New York Herald proclaimed. “The intelligence . . . is cheering enough to welcome in the Fourth of July with appropriate rejoicing!” Newspapers ranging from the Philadelphia Enquirer, to the Cleveland Morning Leader, to the Chicago Tribune printed specifics about the second day’s battle from both their correspondents and Meade’s reports. The news was sometimes inaccurate, such as reports that Confederate General Longstreet was dead or captured. Yet the broad details were solid: The fighting had been some of the fiercest of the war, the Confederates launched their biggest assault around 4 p.m. on the Union left, the Army of the Potomac had been forced back, Union General Dan Sickles had lost a leg, and Confederate General William Barksdale was dead. Most importantly, at the end of the day the Yankee lines had held.12

The most memorable reports on July 4 came from Lorenzo Crounse. “For seven hours without cessation the army of the Potomac has been tried by the fire,” he wrote at midnight on July 2. “It has suffered terribly, but has beaten the enemy in the hardest fight it has yet seen.” His nighttime description of the battlefield was haunting, and his report included a minor but particularly interesting observation: One corps of the army was stationed in “a beautiful cemetery on a hill south of Gettysburgh,” he wrote. “Cannons thundered, horses pranced, and men carelessly trampled over the remains of the dead. From this hill a beautiful view could be obtained of the valley, [but] also of a goodly portion of the enemy’s line of battle.” This was Evergreen Cemetery, and soon there would be another burial ground very near it. This was likely the first description that most Americans had of an area of the battlefield soon immortalized by Abraham Lincoln and the battle’s honored dead.13

The third day’s details were sketchier, especially since many correspondents sent their stories before the Pickett-Pettigrew charge. Therefore, some papers were cautious about declaring complete victory. The Chicago Tribune maintained that while the details were encouraging, they were still “not clear as to the results.” Not until July 6 did most papers have full reports about all three days. Perhaps the best were by Charles Coffin of the Boston Journal and Whitelaw Reid of the Cincinnati Gazette.14

Many southern papers also had correspondents with their army, such as the Richmond Enquirer, the Charleston Mercury, and the Savannah Republican. Their reporters lost contact once Lee crossed the Potomac, however, and did not reestablish it until around July 20. The papers were skeptical about the information they gleaned from the northern press. The Charleston Mercury asserted, “Our people have seen enough of the systematic lying of the Yankee Government, Generals and newspapers, to pay little heed to” their reports. The Richmond Enquirer believed the news was inaccurate because it had been hastily transmitted. “The infernal invention of the electric telegraph,” the editors opined, “…is one of the worst plagues and curses that has ever befallen this human race.” Southern papers accepted any news indicating that their army had fought well, ignoring the rest. As a result, on July 10 the Charleston Mercury proclaimed, “a brilliant and crushing victory achieved by the army under Gen. Lee!” Not until their correspondents made it back to Virginia did the truth arrive, and so it was late July before they acknowledged Lee’s defeat. “We must accept [the results] of the campaign with Southern manliness,” the Mercury’s correspondent declared on July 22.15

Despite southern resistance to the early reports, the age of telegraph and the efforts of intrepid reporters insured that Americans were relatively well informed as Lee invaded Pennsylvania. Between June 29 and July 2, however, the details slowed, and July 3 was a stressful day of anxiety. Yet this only heightened the exhilaration northerners felt on that Fourth of July 150 years ago (especially when Vicksburg news arrived that night), making it all the more appropriate that Lincoln later harkened to the Revolution in his Gettysburg Address.

Glenn David Brasher is the author of The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans and the Fight for Freedom (2012) and winner of the 2013 Wiley-Silver Prize from the Center for Civil War Research.

1 New York Herald, June 27, 1863; Philadelphia Enquirer, June 9, 1863; New York Times, June 28, 1863.

2 New York Tribune, June 26, 1863.

3 Pittsburgh Chronicle, June 25, 1863.

4 New York Times, June 29, 1863.

5 New York Times, June 29, July 1, 1863. See also Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1863.

6 Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1863; New York Times, June 30, 1863.

7 New York Tribune, July 1, 1863.

8 Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1863. See also New York Tribune, July 2, 1863; New York Herald, July 2, 1863; Baltimore Sun, July 2, 1863; Philadelphia Enquirer, July 2, 1863.

9 New York Times, July 2, 1863 [late edition].

10 New York Tribune, July 7, 1863; See also, Noah Andre Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage (New York: Harper Collins, 2010), 432-433.

11 See, for example, New York Times, July 3, 1863; Chicago Tribune, July 3, 1863.

12 New York Herald, July 4, 1863. See also Cleveland Morning Leader, July 4, 1863.

13 New York Times, July 4, 1863.

14 Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1863, Boston Journal, July 6, 7, 1863, Cincinnati Gazette, July 6, 1863.

15 Richmond Enquirer, July 10; Charleston Mercury, July 9, 10, 18, 22, 1863.

Photo Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs (loc.gov)